Feature your business, services, products, events & news. Submit Website.

Breaking Top Featured Content:

How COVID Forbearance Gave Banks A Three Trillion Dollar Boost

Tyler Durden

Wed, 11/04/2020 – 15:24

By Nick Dunbar of Risky Finance

If there was one thing that regulators were sure about at the start of the pandemic, it was that it would not become a bank story. Crisis yes, maybe even a touch of market turmoil for a few weeks in March, but never something that would embroil the world’s mightiest financial institutions, the way that subprime mortgages embroiled them 12 years before.

So starting in March, a series of emergency measures were rolled out that temporarily eliminated or blunted restrictions on bank balance sheets, along with ramped up support for financial markets that in the US at least, was unprecedented. Risky Finance joined forces with Washington DC-based advocacy group Americans for Financial Reform to analyze some of the impact on the six biggest US banks.

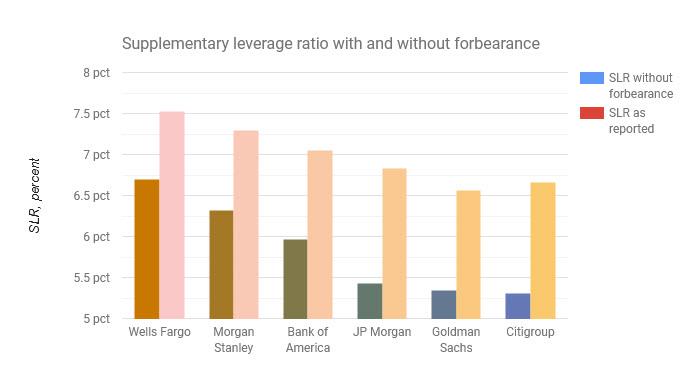

Our research showed that the key limiting constraint this year for the banks has been the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR), part of the 2012 Dodd-Frank Act that harmonised US bank regulation with global Basel rules. The Federal Reserve sets the regulatory minimum SLR at 5%. At the end of June, the top six banks had an average SLR of 7%, comfortably far from the minimum.

However, without three critical forbearance measures, some banks such as Citigroup or Goldman Sachs would have been just 30 basis points away from the minimum, which would prompted the Fed to restrict their trading and lending activity.

Some of the forbearance measures increased the numerator of the ratio, the Tier 1 capital of the bank, while another reduced the denominator, the leverage exposure measure. But if we imagine the effect to have been purely in the denominator, then it would be equivalent to reducing the regulatory balance sheets of the six banks by almost $3 trillion.

Now that’s not such a bad thing, you might say, if it allowed the banks to keep lending and trading in the face of a pandemic which so far has killed 1.2 million people globally.

The biggest forbearance measure was a move by the Fed in May to exclude treasury bonds and central bank deposits from the leverage exposure measure. That wiped $2 trillion off the SLR denominator, including $619 billion at JP Morgan alone.

That followed the Fed’s move in March to allow US banks to delay the impact of IFRS 9 current expected credit loss estimates on their CET1 capital. Even though the six banks have collectively increased CECL by $58 billion this year, a resulting $20 billion reduction in their CET1 has been postponed as a result of the Fed’s decision.

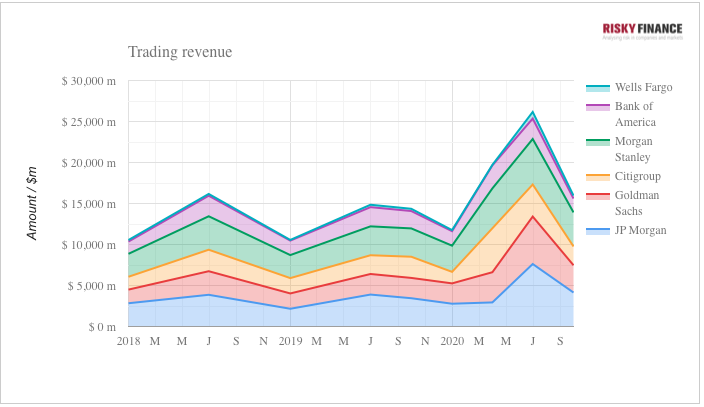

Perhaps more controversial though, is what was not a direct easing of capital requirements. The underpinning of markets, in particular the Fed’s buying of $3.5 trillion of bonds, including corporate bonds, had the effect of compressing credit spreads and suppressing volatility. That allowed banks to make outsized trading revenues, which we can see in the chart below.

In our joint study with AFR, we compared this year’s revenues to the average for the previous, pre-pandemic period. In the absence of regulatory intervention, the banks might suffer trading losses. If emergency action by central banks normalized the markets, you might expect the banks’ trading revenues to be at a ‘normal’ level too.

That’s not what happened though. Led by JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs, the six banks collectively made $19 billion of revenues in excess of this average in the first three quarters of 2020. That wasn’t all. Buoyed by Fed support of the market, by the middle of the year the banks were able to offload corporate loan exposure that otherwise would have stayed on their balance sheets.

This appeared as a bonanza in investment banking revenues, which exceeded the average by $4 billion over the same period. Combined with trading income, this amounts to $23 billion of excess revenues, which directly flows into capital as retained earnings, and can then be used to bolster share buybacks, dividends and bonus payouts.

In hindsight, was it worth it? Having a full-blown financial crisis during the pandemic was best avoided. However, Dodd-Frank and other post-Lehman financial reforms were intended to insulate banks from another crisis. If the position of the banks was so weak going into the pandemic that $3 trillion of support (direct and indirect) was needed to protect them, we can surely ask the question: Should capital requirements on banks go further?

That’s a question that deserves to be in the inbox of the next US president.

Continue reading at ZeroHedge.com, Click Here.