Feature your business, services, products, events & news. Submit Website.

Breaking Top Featured Content:

Connecting the Seward and Glenn highways scarred Fairview. Now, lots of agencies want to make it right.

For the past year, Allen Kemplen has been doing a personal experiment, almost exclusively walking, biking or using city buses to get around. He’s the president of the Fairview Community Council.

Because two of Alaska’s major highways connect in Anchorage’s Fairview neighborhood, it’s a dangerous place for this. On Gambell Street, the sidewalks are too narrow for two people to walk side by side. On a recent walk, only a few inches of snowy curb separated Kemplen from four lanes of cars and trucks whizzing by that drowned out conversation. Some older buildings here come right to the sidewalk, leftover from when Gambell was more pedestrian-oriented. On one stretch, pedestrians and cyclists have to go into the road because of utility poles.

“You have this, you know, monster-ass utility pole right in the sidewalk,” Kemplen said.

Gambell and its one-way counterpart Ingra Street have had a huge impact on Fairview, stifling investment, physically dividing the neighborhood and creating hotspots for fatal car and pedestrian crashes. Now, lots of agencies want to re-envision what this part of Fairview should look like, with some special attention on how these roads impacted this community of color.

“The couplet, it’s created a huge gash in the urban fabric of our neighborhood,” Kemplen said.

He calls the area caught between the two high-volume roads “kind of a wasteland.” It isn’t actually, but some homes and shuttered businesses here have definitely seen better days.

It wasn’t always this way. Fairview developed in the 1940s and 1950s, before the New Seward Highway and Glenn Highway were built. Back then, Gambell had a walkable, Main Street feel, lined with small shops and single-family homes.

It was also the Jim Crow era, when racial discrimination was legal. Unlike most Anchorage bowl communities, people of color could live and own property in Fairview. It’s still one of the most diverse neighborhoods in the city.

After the Good Friday earthquake in 1964, city planners targeted the area for urban renewal. That included turning Gambell and Ingra into the four-lane, one-way roads that chop up the community.

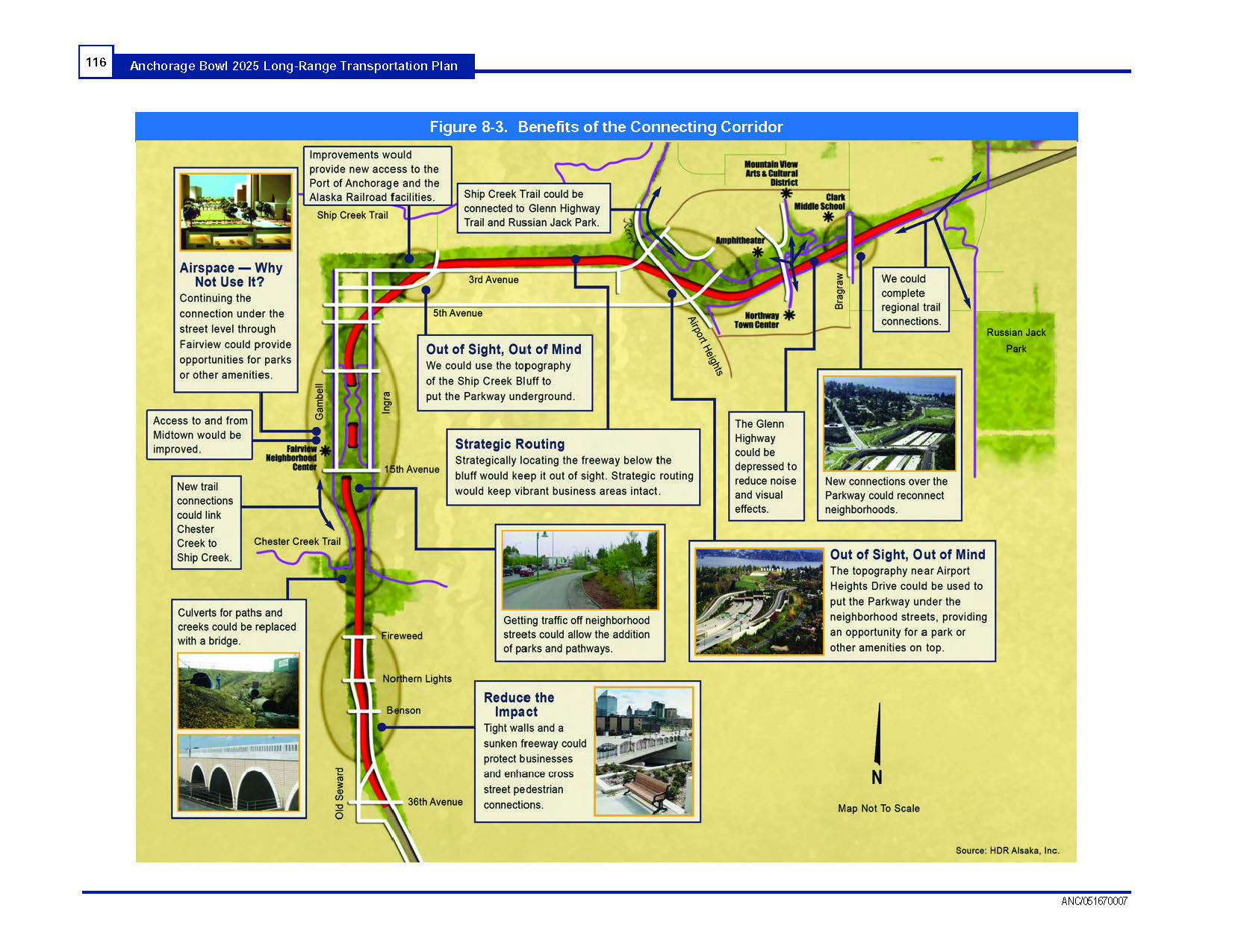

Long-term transportation plans published in 2005 suggested building a high-speed expressway through the properties in between. But it proposed building that road below street level, and covered to allow for redevelopment on the surface. It was a lofty idea, estimated in 2018 to cost about $663 million. Kemplen said it also further discouraged investment in the properties that stand in the way. That expensive concept is still in current long-range transportation plans, but it’s just an unfunded idea.

Right now, there are at least two targeted efforts underway to map out the future of Fairview. The U.S. Department of Transportation announced last month that it’s giving Kemplen’s community council and its nonprofit partner a $537,660 grant specifically for repairing damage to the community from past transportation projects. This Reconnecting Communities grant was borne out of the federal infrastructure bill.

Fairview resident and state Sen. Löki Tobin said winning the grant was an important acknowledgment in and of itself.

“That the historic practices of Federal Highway Administration in communities of color was to use their overarching power to bifurcate brown neighborhoods and suppress housing prices, suppress economic opportunity and vitality, to really re-institute racist policies,” she said.

Transportation engineers usually design projects around traffic counts and use patterns – not social equity and environmental justice. But Tobin said these issues are elephants in the proverbial room that the grant will help address.

Kemplen hopes to use the grant to bring design and planning experts to Fairview for a series of community workshops. He wants to explore innovative and creative ways to develop Fairview as a vibrant winter city.

At the same time, AMATS is working on a study of the corridor that leans heavily on public input. AMATS is a metropolitan transportation planning organization led by a mix of state and municipal officials. If its study stays on schedule, then next year policymakers will have a short list of well-vetted options to connect the highways that are faster and safer for everyone, and make the neighborhood more livable.

Kemplen, who is also a retired Alaska Department of Transportation planner, is wary. He said the agency tends to focus on motorists at the expense of everyone else, and he’s afraid state officials will fall back into old habits.

“DOT says, ‘My way: It’s a highway,’” he said with a chuckle.

DOT spokesperson Shannon McCarthy said things have been changing at her agency over time. She thinks Fairview and DOT will be able to align their goals.

“It’s really exciting that they got this grant,” McCarthy said. “With a grant like this, they can do some things that we either don’t typically do, or that we just don’t have in our wheelhouse. So I think that the two efforts can and will work well together.”

Some of Fairview’s interests are already guiding the work; one cornerstone of the DOT study cemented in January is to promote social equity.

And, remember those utility poles blocking the sidewalk? McCarthy said they’ll be removed when the utility lines go underground in the next year.