Feature your business, services, products, events & news. Submit Website.

Breaking Top Featured Content:

The Spectre of Inflation

THE SPECTRE OF INFLATION

The ‘creeping’ enemy of wealth — Financial Literacy 101

Inflation terrifies people for a lot of reasons, including its erosion of the purchasing power of wages and the value of dollar-denominated debt. But in May, a leading foreign exchange trader named Stanley Druckenmiller warned of an even bigger long-term risk of inflation: That it might threaten the U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s dominant “reserve currency”.

David Morris: Druckenmiller’s Inflation Warning Good for Crypto — CoinDesk

The U.S. dollar $ is overwhelmingly the preferred currency for international trade — just think for instance to the huge global oil trade is dollar-denominated and settled. The dollar is also the most widely held foreign currency in central banks.

This produces major economic benefits for Americans — which represent an enormous privilege for them, both holders and beneficiaries of the U.S. dollar — and its decline could harm the U.S. economy.

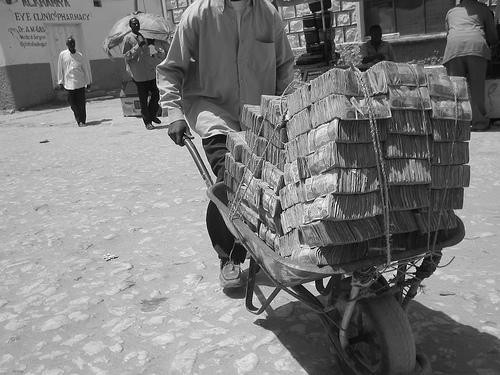

We’re still miles away from the kind of hyperinflation that can truly wreak havoc on both the currency or the economy, as shown in the real-life cases around the world in countries such as Lebanon (144.1%), Venezuela (1743%), and Argentina (50%) just to mention a few, and the most acute cases of hyperinflation recorded to this day.

Argentina’s annual inflation rate tops 50% as global prices soar | Reuters

Venezuela subtracts six zeros from currency, second overhaul in three years | Reuters

Lebanon follows Venezuela into hyperinflation wilderness | Reuters

There’s also a lot of evidence that current U.S. inflation is highly concentrated in a few sectors, and bond investors have remained stubbornly and tenaciously skeptical about inflation being just ‘transitory’, despite concerns of its higher-than-expected rates.

The Fed’s use of ‘transitory’ to describe inflation may be ‘transitory’ — CNN

But whether inflation pushes things along or not, it’s clear the dollar’s reserve status is already under pressure.

INFLATION UNCOVERED

So, what exactly is INFLATION?

Does it feel like a dollar buys less than it used to? You’re not imagining things. “It’s inflation,” people moan.

Inflation is an increase in the prices of goods and services in an economy over a period of time.

That means you lose buying power — the same dollar (or whatever currency you use) buys less and is thus worth less.

In other words: With inflation, your money doesn’t go as far as it used to.

Example: If apples cost 25 cents a piece, one dollar buys four of them. But say apples become scarcer or more expensive to grow, and the next year, the grocer prices them at 50 cents apiece. Now one dollar buys only two of them. In purchasing-power terms, the dollar has effectively lost half its value (at least as far as apples are concerned).

Remember that modern money really has no intrinsic value — it’s just paper and ink, or, increasingly, digits on a computer screen. Its value is measured in what or how much it can buy.

While it’s easier to understand inflation by calculating goods and services, it’s typically a broad measure that can be applied across sectors or industries, impacting the entire economy. In fact, one of the primary jobs of the Federal Reserve is to control inflation to an optimum level to encourage spending and investing instead of saving, thereby encouraging economic growth.

GAUGING INFLATION

Inflation is calculated by adding up the prices of thousands of different things and comparing them to the prices for the same goods a month ago.

This means there is a list somewhere of the specific things that count towards inflation in your country, and each month someone has to go out and check the prices of all these things.

The two most frequently cited indexes that calculate the inflation rate in the U.S. are:

- the Consumer Price Index (CPI);

- the Producer Price Index (PPI);

- the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCE).

Let’s look at them in detail.

CPI — Consumer Price Index

The US Bureau of Labor Statistics measures the inflation rate using the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The CPI measures the total cost of goods and services consumers have purchased over a certain period, using a representative basket of goods, based on household surveys. Increases in the cost of that basket indicate inflation and using a basket accounts for how prices for different goods change at different rates by illustrating more general price changes.

PPI — Producer Price Index

In contrast with the CPI, the Producer Price Index (PPI) measures inflation from the producer’s perspective. The PPI is a measure of the average prices producers receive for goods and services produced domestically. It’s calculated by dividing the current prices sellers receive for a representative basket of goods by their prices in a specific base year, then multiplying the result by 100.

PCE — Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index

The PCE measures price changes for household goods and services based on GDP data from producers. It’s less specific than the CPI because it bases price estimates on those used in the CPI, but includes estimates from other sources, too. As with both other indices, an increase in the index from one year to another indicates inflation.

THE CAUSES OF INFLATION

There’s massive economic literature on the causes of inflation, and it’s fairly complex.

Basically, though, it comes down to the principles of supply and demand.

The gradually rising prices associated with inflation can be caused in two main ways: demand-pull inflation and cost-push inflation.

- Demand-pull inflation happens when prices rise from an increase in demand throughout an economy.

- Cost-push inflation happens when prices rise because of higher production costs or a drop in supply (such as from a natural disaster).

Yet other analysts cite another cause of inflation: an increase in the money supply — or, simply put, how much cash, or readily available money, there is in circulation.

Whenever there’s a plentiful amount of something, that thing tends to be less valuable — cheaper. Indeed, many economists of the monetary school believe this is one of the most important factors in long-term inflation:

Too much money around the supply devalues the currency, and it costs more to buy things.

M1 (M1SL) | FRED | St. Louis Fed (stlouisfed.org)

INFLATION & THE FED — a love/hate relationship

The Federal Reserve is the central bank of the U.S., and the Fed — like central banks around the world — is tasked with maintaining a stable rate of inflation. The Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC) has determined that an inflation rate of around 2% is optimal for employment and price stability.

This level of inflation gives the FOMC scope to jump-start the economy during downturns by decreasing interest rates, which makes borrowing cheaper and helps boost consumption.

Lower interest rates reduce costs for businesses and consumers to borrow money, stimulating the economy.

Lower interest rates also mean individuals earn less on their savings, encouraging them to spend.

But all this extra demand can push up inflation.

TAMING A WILD HORSE

When inflation isn’t kept in check, it’s commonly known as hyperinflation or stagflation. These terms describe out-of-control inflation that cripples consumers’ purchasing power and economies.

HYPERINFLATION

It refers to a period of extremely high inflation rates, sometimes as much as price rises over 50% per month for several months. Hyperinflation is usually caused by government deficits and the over-printing of money.

In a modern case, Venezuela is experiencing hyperinflation, reaching an inflation rate of over 800.000 % in October 2020.

Venezuela’s annual inflation hit 833,997 percent in October: Congress | Reuters

STAGFLATION

On the other hand, we have a rare event in which rising costs and prices are happening at the same time as a stagnant economy — one suffering from high unemployment and weak production.

The US experienced stagflation in 1973–1974, the result of a rapid increase in oil prices in the midst of low GDP.

Stagflation and the oil crisis (article) | Khan Academy

THE BAD, THE UGLY AND … QUANTITATIVE EASING

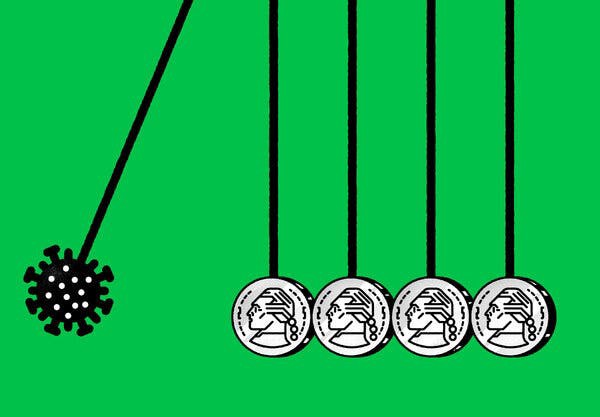

When a central bank decides to use Quantitative Easing (or QE), it makes large-scale purchases of financial assets, like government and corporate bonds and even stocks. This relatively simple decision triggers powerful outcomes:

Firstly, the amount of money circulating in an economy increases, which helps lower longer-term interest rates, and secondly, it lowers the cost of borrowing, which spurs economic growth.

This is the goal of QE: by buying longer maturity securities, a central bank is aiming to lower longer-term market interest rates. Contrast this with the main tool used by central banks: standard rate policy, which targets shorter-term market interest rates.

When the U.S. Federal Reserve uses standard rate policy, it adjusts its target for the federal funds rate. The goal here is to influence the short-term rates that banks charge each other for overnight loans. The Fed has used interest rate policy for decades to keep credit flowing and the U.S. economy on track.

But when the federal funds rate dropped to zero during the Great Recession — making it impossible to cut further to encourage lending — the Fed deployed QE and began purchasing mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and Treasuries to keep the economy from freezing up.

With QE, Central Banks are sending a powerful message to the economic markets participants, are telling them that they’re not afraid to continue buying assets to keep interest rates low.

QE: THE POSSIBLE CAUSE FOR THE RAMPANT INFLATION?

When financial institutions collapse, and there is a high degree of economic uncertainty, people and businesses choose to stockpile their money rather than risk investment and potential loss. When money is hoarded, it is not spent and so producers are forced to lower prices in order to clear their inventories.

But why would somebody spend a dollar today when they expect that prices will be lower — and their dollar can buy effectively more — tomorrow?

The result is that hoarding continues, prices keep falling, and the economy grinds to a halt.

The first reason, then, why QE did not lead to hyperinflation is because the state of the economy was already deflationary when it began.

As Milton Friedman put it, “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”.

If inflation was a monetary phenomenon, then controlling the supply of money was the route to low inflation. Monetary aggregates became central to the conduct of monetary policy, but the passage to low inflation is rather a painful path.

So, as central banks became more and more focussed on achieving price stability, less and less attention is paid to movements in money. Indeed, the decline of interest in money appeared to go hand in hand with success in maintaining low and stable inflation.

But if doubling the amount of money somehow caused a huge surge in economic growth, it has brought to attention some serious problems, which seem getting harder and harder to respond to, due to the deep ‘addiction’ of government economic policies to depend on QE:

1) Inflationary pressures over long-term:

When a central bank prints money, the supply of dollars increases. This hypothetically can lead to a decrease in the buying power of money already in circulation as greater monetary supply enables people and businesses to raise their demand for the same amount of resources, driving up prices, potentially to an unstable degree.

2) It may cause Asset Bubbles:

Quantitative easing can cause the stock market to boom, and stock ownership is concentrated among Americans who are already well-off, crisis or not. By lowering interest rates, the Fed encourages speculative activity in the stock market that can cause bubbles, and the euphoria can build upon itself so long as the Fed holds pat on its policy.

3) It causes INEQUALITY:

The final danger of QE is that it might exacerbate income inequality because of its impact on both financial assets and real assets, like real estate; it does aggravate the situation of a deeply fragmented, poorly connected major ‘minority’ whom find themselves in already precarious financial situation and have little or no access to any financial services or form of wealth preservation.

GENERATIONAL FIGHT

We established the harsh truth of the matter:

INFLATION ERODES THE INDIVIDUAL PURCHASING POWER OVER TIME

So the money we earn through our activities has to keep earning. Investing seems to be the best way to face and potentially keep up the fight against inflation.

When investing, the smart & responsible investor should focus his/her attention on assets that deliver a rate of return that outpaces the inflation rate.

Certain types of assets may beat inflation better than others, such as:

- Stocks: there are no guarantees with the stock market, but overall and over time, share prices appreciate at a rate that typically exceeds the inflation rate. Most index funds also post returns better than inflation.

- Inflation-indexed bonds: most US Treasuries pay the same fixed amount of interest — whose value erodes if inflation is rampant.

- Physical assets and commodities: alternative investments — often, tangible assets like gold, commodities, fine art, or collectibles — do well in inflationary environments. So does real property, notably in the form of real estate.

INFLATION AS ‘MOTIVATION’

We saw how QE has been “hugely effective” in the early parts of both the most recent coronavirus crisis and the financial crisis, keeping the market afloat and actually promoting growth (although at a sluggish rate)

But at what cost?

Once the market has stabilized, the risk of QE is that it could create a bubble in asset prices, adding to already established realities of imbalances in income inequality in the majority of the countries.

The impact of inflation may seem small in the short term, but over the course of years and decades, inflation can drastically erode the purchasing power of people’s savings; a modest amount of inflation is completely necessary for economic growth but knowing what the inflation rate is, whether it’s high or low, can help guide the individuals’ money decisions.

Check out our new platform 👉 https://thecapital.io/

https://twitter.com/thecapital_io

The Spectre of Inflation was originally published in The Capital on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.