Feature your business, services, products, events & news. Submit Website.

Breaking Top Featured Content:

Zoltan: JPM Stockpiled Cash As BofA Was Only Bank Buying Treasuries In Q2

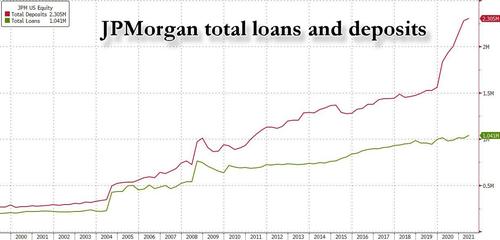

Back in March, the market briefly paid attention to the fate of the Supplemental Liquidity Ratio ahead of its 1-year post-Covid maturity and then when it expired without much market turmoil, quickly forgot all about it. But not the banks, and no one more so than JPMorgan, which instead of investing its massive excess cash stockpile spawned by a record flood of deposits (discussed here over the weekend) in treasuries as it traditionally does… did nothing for a variety of reasons discussed below.

Speaking after JPM’s earnings call last week, JPM CEO Jamie Dimon said the largest US bank continues to stockpile cash instead of investing it in securities, such as U.S. Treasuries and mortgage-backed bonds, which pay more than cash deposits.

To be sure, how the country’s largest lenders manage an unprecedented glut of cash piling up on their balance sheets will be important in separating winners from losers in coming quarters as uncertainty grows over the inflation and interest rate outlook, analysts said.

“The balance sheet mix will be a key driver for the stocks as we move into 2022,” David Konrad, an analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, wrote in a report to clients. “In our view, the risk/reward favors holding cash and under- earning in this environment.”

To be sure, there are many reasons behind the cash hoarding. Speaking to analysts on Tuesday, JPM CFO Jeremy Barnum said that the bank is waiting for the chance to buy securities with higher yields once exceptionally strong economic growth kicks in and drives up inflation and interest rates. In light of the ongoing collapse in yields (and surge in prices), this has so far proven to be a painful decision.

“You may have growth in the second half this year that’s stronger than it’s ever been in the United States of America,” Dimon said last Tuesday. Less than a week later, the market is panicking that not only is the best of the post-covid growth burst behind us, but that the Fed may be forced to push back substantially on both its tapering and its rate hikes as the US economy contracts. As a result, the yield on 10-year Treasury notes, at around 1.35% last Tuesday vs 1.75% in March, could climb to 3%, Dimon added. A few days later it is down to 1.17%.

Dimon’s comments came after JPMorgan posted quarterly financials on Tuesday that showed its average cash balance held on deposit at central and other banks increased by $89.6 billion while it added only $2.6 billion of investment securities. This is hardly an optimal allocation for a bank collecting net interest income: JPMorgan made 0.06% on its cash while its securities paid 1.31%, its reports showed.

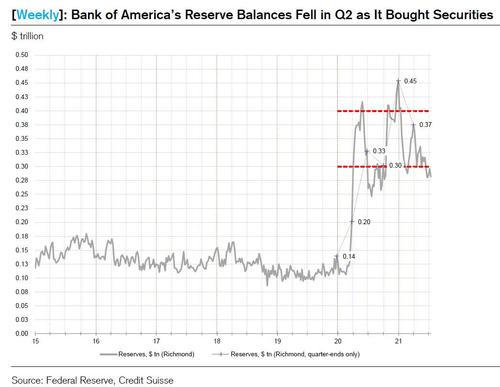

In contrast, Bank of America Corp’s results released on Wednesday showed it has let its cash decline by $31 billion while it added $107.3 billion to its securities holdings. “The reality is that we generated $80 billion deposit growth, and we’ve got to put it to work,” CEO Brian Moynihan told analysts. Unlike JPM, the BofA CEO said that “we’re not timing the market or betting.”

As observed last week, JPMorgan’s deposits grew by nearly $100 billion during the quarter while its loan were flat, as new cash created from the Fed’s QE ended up on the bank’s balance sheet via the depositor pathway.

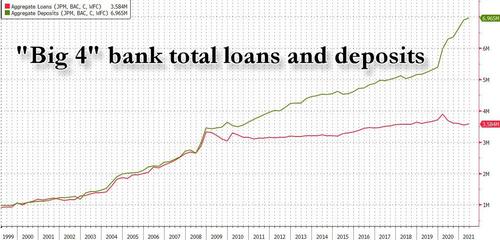

Meanwhile, cash from government stimulus and Federal Reserve programs continues to pour into the financial system, dampening demand for bank loans which at the sector level are effectively unchanged since the global financial crisis 13 years ago.

As Reuters notes, analysts had pressed bank execs about their cash and securities mix because of how important proper capital allocation is for profits. Banks often hedge their positions with derivatives, making the analysis more difficult.

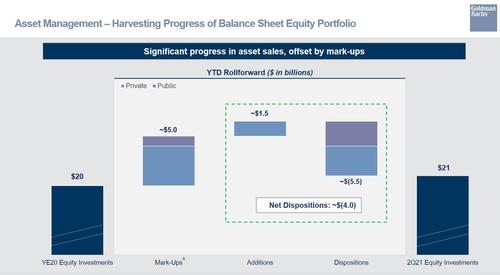

For their part, bank executives have warned of tradeoffs in the decision on how much cash to accumulate until rates rise, and how much to invest in securities now. Clearly in the case of JPM it’s virtually no investments. Elsewhere, in the case of Goldman Sachs, we saw that the bank had quietly liquidated a quarter of its equity investments, and whether in anticipation of a market rout or simply for capital allocation reasons, the bank was also very cash heavy entering the third quarter.

Other considerations include ensuring liquidity for customers who take deposits back and guarding against hits to regulatory capital from declines in the value of purchased securities.

Going back to Dimon, speaking at a conference last month, he said that “JPMorgan’s decision to stockpile cash was “purely discretionary,” adding that “you’ll find out one day whether we made the right decision or not.” Well, if today is the day then the decision is clearly wrong. And if yields keep dropping it will keep getting worse.

Dimon’s traditional cockiness notwithstanding, the topic of bank capital allocation was also the highlight of the latest Global Money Dispatch note from the now iconic repo guru, Zoltan Pozsar, who is quite familiar to our readers and who recently was profiled extensively by the WSJ.

As Zoltan observes, the balance sheets of the largest U.S. depository institutions including J.P. Morgan, Bank of America, Citibank and Wells Fargo, didn’t grow much during the second quarter:

across the board, total on balance sheet assets were flat, or up by a “rounding error”; assets other than HQLA (reserves and securities) were up by about $30 billion on average, driven by some signs of recovery in loan growth on the back of stronger demand, but given that we are talking about balance sheets that are $2-3 trillion in size, this growth is nothing really;

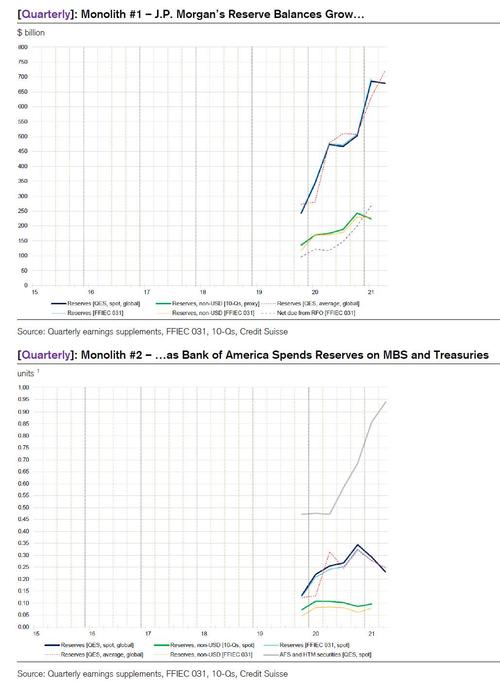

Meanwhile, and in keeping with the abovementioned cash stockpiling, reserve balances were down everywhere but J.P. Morgan while reserve balances fell the most at Bank of America as the bank spent $60 billion of reserves and another $20 billion on incoming deposits on Treasuries and MBS. At the same time, deposit growth slowed to its slowest pace during the pandemic, as QE and the decline in Treasury’s cash balances during the second quarter injected mostly low-quality deposits into the system which banks pushed into the RRP facility; finally, bank capital growth slowed dramatically too, as banks started to return earnings to shareholders by increasing their dividends and share buybacks.

Summarizing these shifts, the former NY Fed analyst notes that things are currently mostly changing on the margin: “the quantum of CET1 capital banks will run with will flatline from here as banks resume their pre-pandemic behavior of passing on practically all earnings to shareholders” at least until we get the abovementioned SLR relief. This means that large banks’ balance sheet capacity to add deposits and HQLA (reserves and securities) will be static from here and will lead to even greater builds in the Fed’s reverse repo facility as the Fed keeps injecting $120BN in reserves every month.

Pozsar also focused on two additional themes from this week’s earnings calls: one regarding J.P. Morgan’s G-SIB surcharge for this year, and one regarding the approach that guides securities purchases at J.P. Morgan versus the approach that guides securities purchases at Bank of America.

First, on G-SIB: J.P. Morgan’s management indicated that they will try to get their G-SIB surcharge under 4.5% for this year – it finished the first quarter just under the 5% G-SIB threshold. This, according to Pozsar, means that “it’s likely that J.P. Morgan will do the usual “maneuvers” that lead to pressures around year-end.”

Second, the approach to securities purchases: as noted above, JP Morgan times the market (it buys when yields are high), and Bank of America buys regardless of yields (it buys to earn net interest income (NII) when loan growth is largely dormant).

That’s why Bank of America bought $40 billion of Treasuries and $40 billion in MBS during the second quarter; J.P. Morgan bought none, and it likely won’t buy any until yields back up to levels well above the second quarter average. Until then, Pozsar concludes that we only have one big marginal buyer of duration: Bank of America.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 07/19/2021 – 16:21

Continue reading at ZeroHedge.com, Click Here.