Feature your business, services, products, events & news. Submit Website.

Breaking Top Featured Content:

The Guiding Principle Of Our Time – CYA!

Tyler Durden

Fri, 10/09/2020 – 16:20

Authored by Louis-Vincent Gave via Gavekal Research,

What is the dominant guiding principle of western societies today?

At the risk of sounding crass, let me suggest that it is the “cover your ass” or CYA principle. This principle has always been fairly prominent in participative democracies. But now it has gone into hyper-drive – so much so, that the CYA principle is also now an important driving force even in financial markets.

CYA and Covid-19

Take the response to Covid-19 as an example of the CYA principle in action. Is there any doubt that the rush to lock down economies and suspend normal civil rights—to go to church, to attend school, to visit friends—in the face of Covid was driven largely by policymakers’ fears that if large numbers of people died, they would be held accountable in the court of public opinion?

Of course, no policymakers want a surge in deaths on their watch. But economies did not get shut down during the 2009 swine flu pandemic, nor during Sars in 2003, the Hong Kong flu pandemic of 1969, nor even the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918. So what changed between the time of Sars and the time of Covid? One obvious answer is the rise of social media.

Now that every policy choice is reviewed and debated in real time by millions of people around the world, CYA has become all-important. Politicians have to put policies in place to hedge against the wildest tail risks imaginable. At the same time, the first instinct of policymakers (and of investors—but more on this later) is to avoid doing anything that diverges too far from the pack. Any policymaker anywhere looking at the opprobrium heaped on Sweden will surely agree with John Kenneth Galbraith’s observation that “it is far, far safer to be wrong with the majority than to be right alone”.

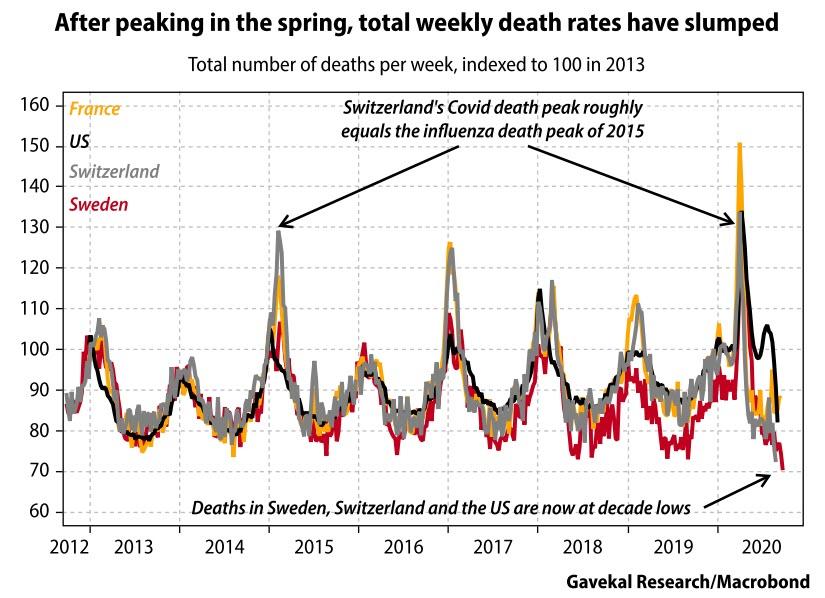

Once Denmark and Norway had decided to follow Italy’s lead and lock down their populations, any western government that did not follow suit risked being accused of playing Russian roulette with people’s lives, regardless of the epidemiological evidence. Unfortunately, we still seem stuck in this mindset, even as the weekly death tolls across western countries have dipped to generational lows, almost regardless of the Covid policies they adopted (see the chart below).

So, we should all be grateful that Donald Trump appears to be bouncing back from his brush with Covid having taken little harm. Firstly, of course, Trump is human, and it doesn’t do to wish harm on another human. Secondly, if Covid were to have taken Trump’s life, it would have claimed the highest profile victim possible. And after the death of the US president, who can doubt that anti-Covid measures would become even more liberticidal. Regardless what you think of Trump, that would be a very bearish development, at least for “Covid-victims” such as energy names, airlines, casinos, hotels, and restaurants, all of which are desperate for policymakers to acknowledge that Covid-19 no longer seems to be as lethal as it was six months ago.

CYA and the fiscal and monetary policy mix

Moving on to the far less controversial fiscal and monetary policy responses to the recession, can there be any doubt—again—that policy is being driven above all by the CYA principle? What policymaker wants to espouse the Hippocratic principle of “first, do no harm,” and let markets and prices find their own footing? None. As Anatole has argued, policymakers are scrambling always to do more, with ever-bigger budget deficits funded by ever-more money printing (see Will A Keynesian Phoenix Arise From Covid?).

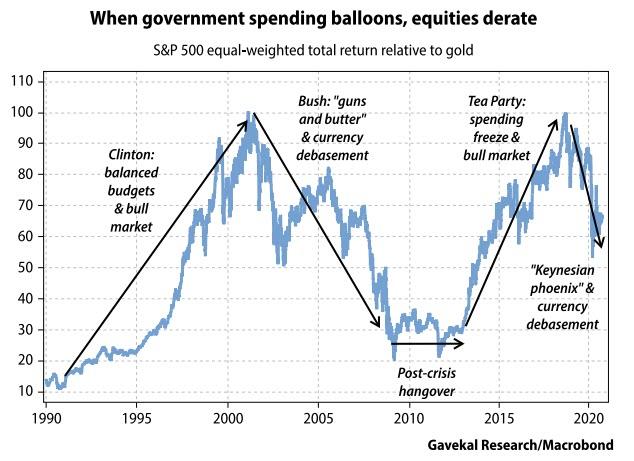

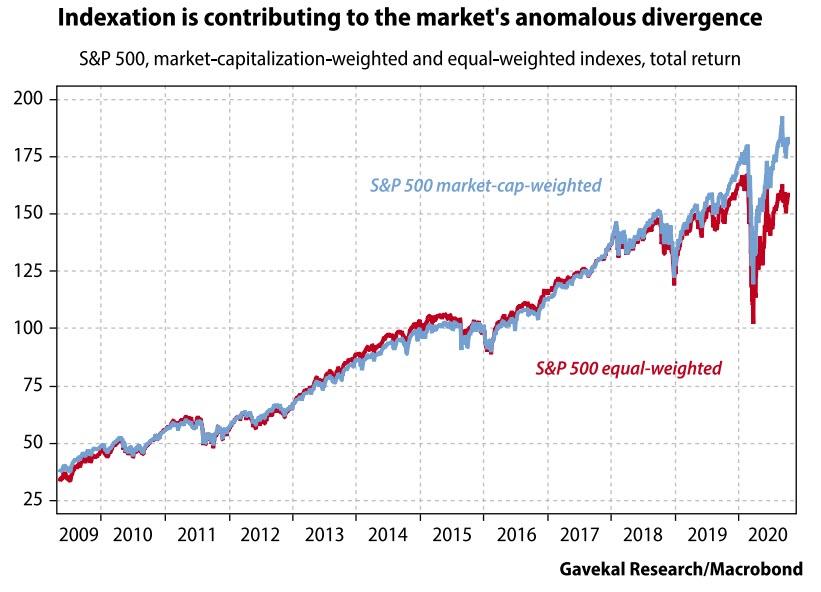

Can this new enthusiasm for budget deficits and money printing guarantee prosperity? It seems to for some individual stocks. But for the broad market? Perhaps not, or at least not in “real terms”. Take the equal-weighted S&P 500 as a proxy for the typical equity portfolio (appropriate now a handful of mega-cap names dominate the cap-weighted index), and discount it by the gold price to get a picture of equity returns adjusted for currency debasement.

When US governments keep spending under control, as Bill Clinton’s did in the 1990s or the Tea-Party-led Congress did after 2011, the broad equity market goes through long phases of “rerating” against gold (see the chart below).

And when the government embraces expanding budget deficits funded by the Federal Reserve, as with George W Bush’s “guns and butter” policies or Donald Trump’s rapid deficit expansion, gold massively outperforms the broad equity market. Where does this leave us today? Since 2014, the equal-weighted S&P 500 has delivered the same returns as a pet rock—gold. This is because the index has lost a third of its value since making a high in September 2018, and has basically been flat-lining since late April (see the chart below).

This may help to put the current debate on US stimulus into context. First, does anyone doubt that the US government will release a tsunami of new spending after the election? Because of the CYA principle, what policymaker will want to be seen to be blocking recovery? Secondly, will this increase in budget deficits, funded by the printing press, trigger stronger economic growth? If so, why weren’t we doing it before? Will it lead to higher asset prices? If so, why are we so far off the 2018 high? Or will it mean further currency debasement? Looking at the ratio between the equal-weighted S&P 500 and the gold price, will a new round of stimulus mean a return to the February 2020 high? Or will it see the March 2020 low taken out?

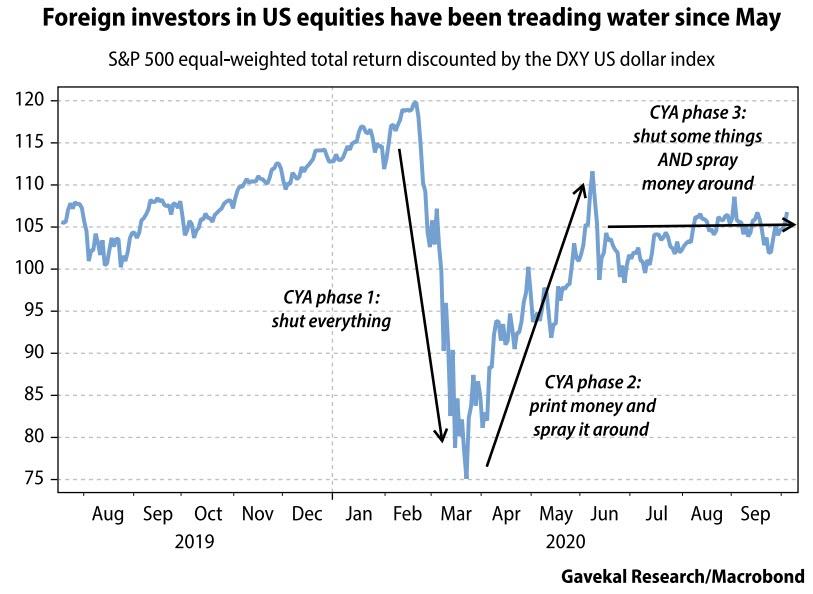

Another way to look at this problem is through the prism of the US dollar. Will another round of fiscal stimulus be dollar-bullish? Or will it be dollar-bearish? The answer matters greatly to all those foreign investors currently seeking shelter in US equities. For them, the return on US equities has been flat since late May – and going further back, flat since mid-2019.

So, if another round of stimulus weakens the US dollar, as seems likely if the stimulus is funded by the Fed, then foreign investors will have to hope that increased equity values will more than compensate for their foreign exchange losses.

CYA and indexing

This brings me to what is likely the most important element of all this for readers: the CYA principle and investing. Gavekal has written at length about the dangers of indexing (see, for example, Exponential Optimization). We have also argued that indexing is the new in-vogue form of socialism. Capital is not allocated according to its marginal return—the foundation on which capitalism rests. Instead, capital is allocated according to the size of companies. Just as in the days of the old Soviet Union or Maoist China, the bigger you are, the more capital you get. It is hard to think of a stupider way to allocate one of the key resources on which future growth relies. So why is indexing so popular? Simple: it is the ultimate CYA strategy.

As Charlie Munger likes to say: “Show me the incentives, and I will show you the outcome.” In a world where every money manager is told his or her target is to achieve a performance close to that of the index, it is hardly surprising that ever-more money ends up getting indexed (see Indexation = Parasitism). As a consequence, over the years the dispersion of results among money managers has become smaller and smaller.

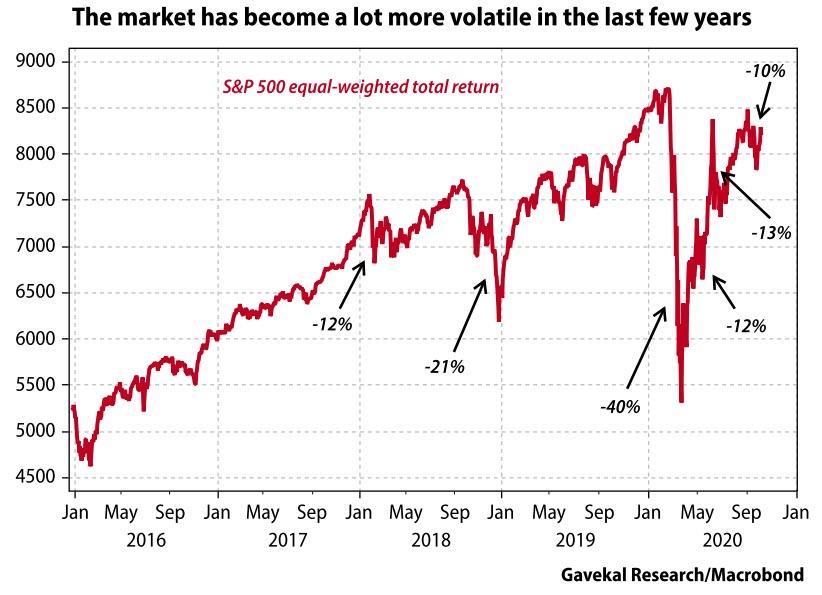

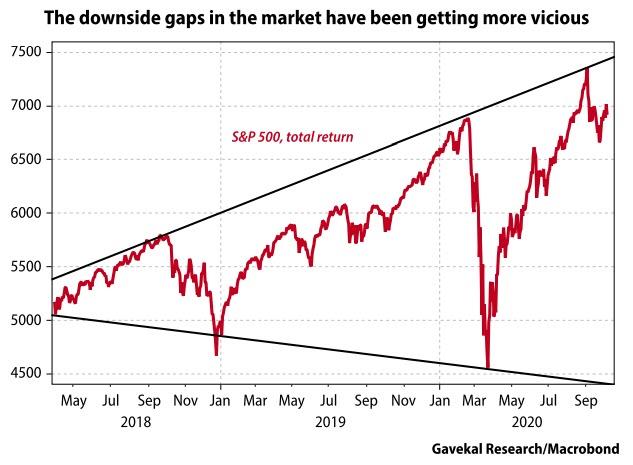

Now, the Holy Grail of money management is to achieve decent long term returns combined with low volatility in those returns. However, in a world where ever-more capital is directed into investments that outperform— playing momentum rather than mean reversion—you inherently end up with greater volatility all round. Take the past few years as an example: since January 2018, the S&P 500 equal-weighted index has suffered six corrections of -10% or greater, including one -20% drop and one -40% drop. In contrast, in the preceding two years—January 2016 to January 2018—the S&P 500 did not see a single -10% drop, while the July 2016 to January 2018 period didn’t even see a -5% drop. Clearly, something in the environment has changed.

More indexing makes sense from a CYA perspective, but ends up delivering lower returns and higher volatility all round. This stands to reason. If capital is allocated only according to marginal variations in the price of an asset, then the more the asset’s price rises, the more capital money managers will allocate to that asset. And the more an asset’s price falls, the less capital is allocated to it. Such momentum-based investing inevitably creates an explosive-implosive system, which swings wildly from booms to busts and back again. And in the process, capital gets misallocated on a grand scale.

In the 20th century, the goal of every socialist experiment was for everybody to earn the same salary. In the 21st century, it seems that the goal of indexing is for everybody to earn the same return. As we now know, fixing everyone’s return on labor at the same price was a disaster. People stopped working, and economic growth plummeted. Fast forward to today, and why should we expect a different outcome if the end-goal of our investment strategy is to ensure that everyone gets the same return, not on the their labor but on their capital? Isn’t the entire world of money management now oriented towards delivering this remarkable ambition?

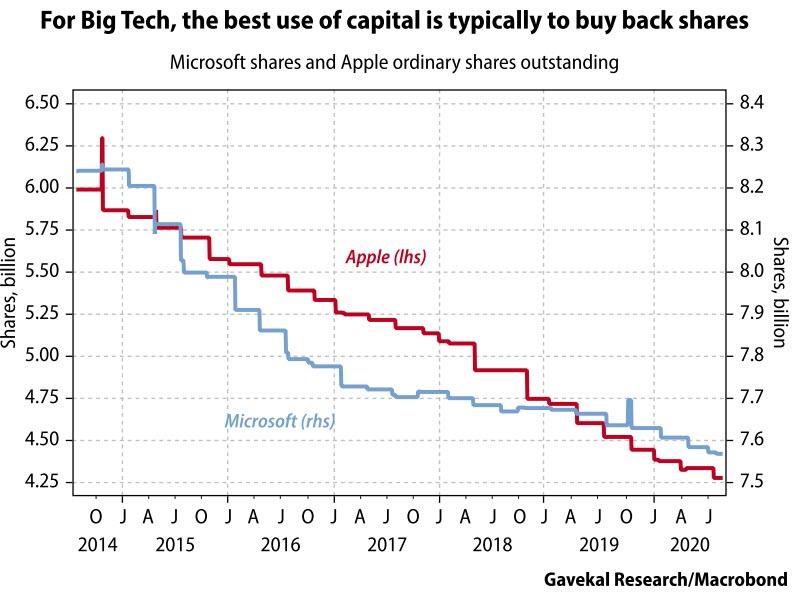

And should we really be surprised if the growth rates of our economies continue to slip? Why should we expect a positive growth outcome from an epic misallocation of capital? Take the current Big Tech craze as an example: everything is organized for investors to sink ever more capital into those very companies that need it least, and whose best use for this gusher of money is typically to buy back their own shares.

This CYA investment-decision-making process appears to be one of the key drivers behind the recent divergence between the S&P 500 market-capitalization-weighted index, and the S&P 500 equal-weighted index.

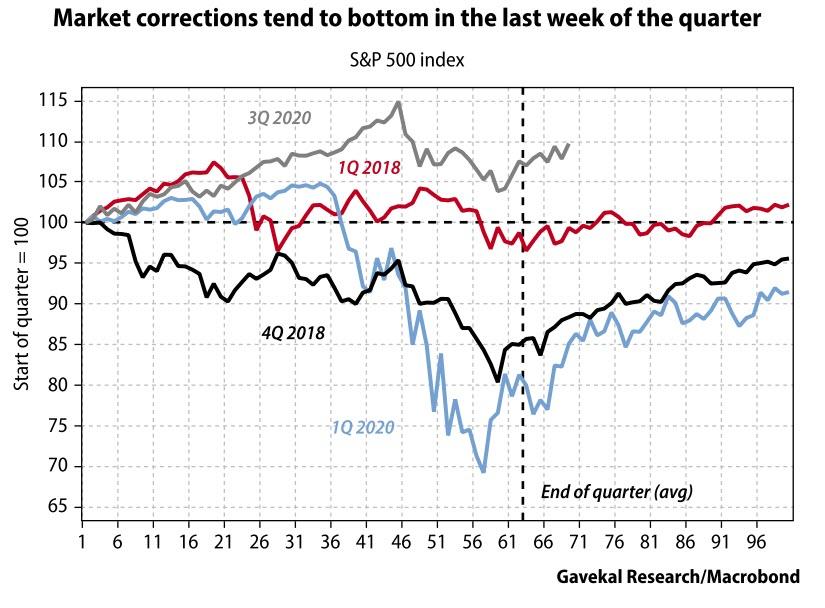

But it may also explain an interesting point raised by my friend Vincent Deluard, strategist at StoneX. In a recent tweet (he’s well worth following) he noted that each of the last four major market corrections bottomed out in the last week of the quarter, just after the index futures expired. Now, this could be a remarkable coincidence. On the other hand, it might say a great deal about how capital is allocated today.

Conclusion

In A Study Of History, Arnold Toynbee reviewed the rise and fall of the world’s major civilizations. He showed that throughout history, when any civilization was confronted with a challenge, one of two things could occur. The elite could step up and tackle the problem, allowing the civilization to continue to thrive. Alternatively, the elite could fail to deal with the problem. In this case, as the problem grew, their failure led to one of three outcomes.

1) A change of elite. An example is the clear-out of the French political class at the time of decolonization. As the old Fourth Republic stalwarts struggled to meet the challenges of Asian and African independence movements, they were replaced by Charles de Gaulle who brought in new personnel and established the institutions of the Fifth Republic.

2) A revolution. Obvious examples include the French revolution, with the bourgeoisie taking over from the aristocracy, and the American revolution, with the local elite taking power from the British king.

3) A civilizational collapse. Examples include the collapse of the Aztec, Mayan and Inca civilizations following the arrival of the conquistadores. Another is the disappearance of the Visigoths in Spain and North Africa following the Arab-Muslim invasions at the start of the eighth century.

With this framework in mind, how does CYA as an organizational policy approach help in dealing with challenges? The obvious answer is that if CYA is your guiding principle, the problems you chose to tackle will be those where there is little controversy within the elite about the required solutions.

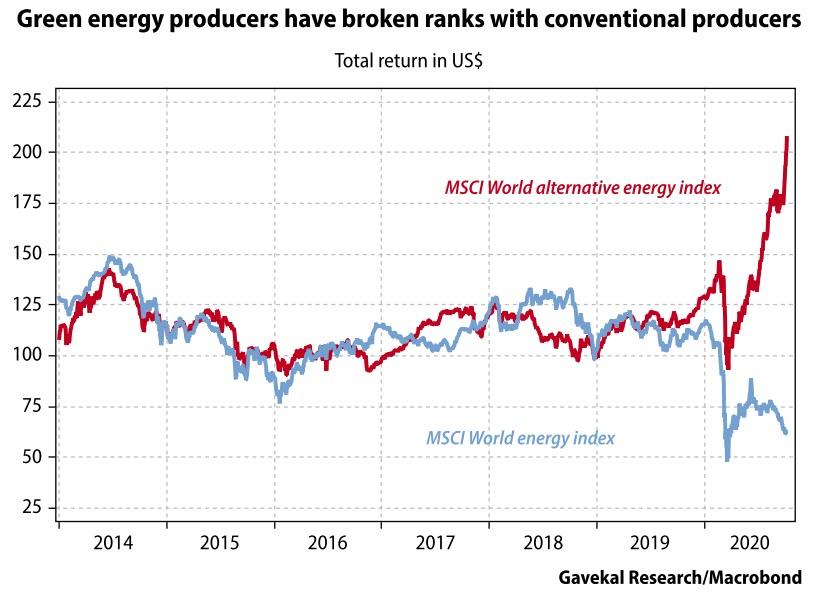

This explains the constant hectoring about tackling climate change. Here, policymakers can promise to spend lots of money, without leaving their backsides too exposed. This accounts for the dramatic divergence between the performance of green energy producers (who produce energy) and carbon energy producers (who also produce energy).

It may also explain the rush towards ever-more European integration, as if the real challenge facing Europe today is a resurgence of the Franco-German rivalry that tore the continent apart in the 19th and 20th centuries. Policymakers can spend entire weekends in summit meetings debating European integration. This allows them to feel useful and important, even if their debates increasingly seem about as relevant as the debates of the Byzantines over the gender of angels even as the Turks were storming their city. But while pushing for more European integration might not tackle any of the issues European voters actually care about, at least it doesn’t leave your behind exposed.

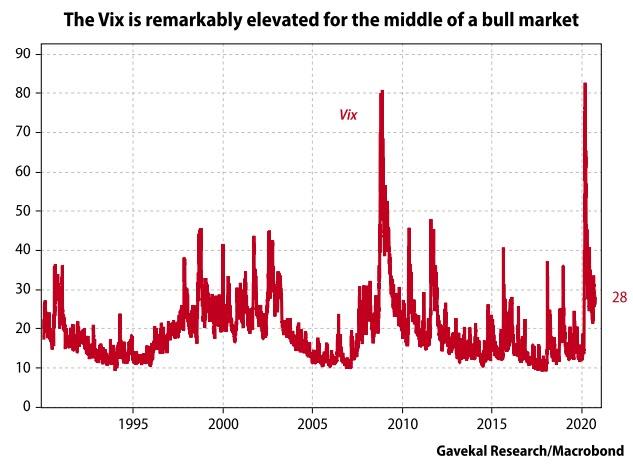

This brings me back to Karl Popper’s theory that at any one time, there is a set amount of risk in the system. Any attempt to contain this risk either displaces it to somewhere else, or stores it up for later. If Popper was right, then the extreme aversion of our policymakers to taking risks means that the risk must appear elsewhere. But where? Perhaps in financial markets? It does seem not only that spikes in the Vix have been getting sharper lately, but that the Vix is also staying more elevated than you would expect in the middle of a roaring bull market.

Or, to put it another way, over the past few years, it does seem that the “downside gaps” in markets have started to become more vicious.

So perhaps CYA makes sense in today’s financial markets. The challenge, of course, has become finding the instruments that allow you to cover your posterior. In March 2020, as equity markets tanked, government bonds did not diversify portfolios adequately. And in September, as equities fell -10% from peak to trough, bonds also failed to deliver offsetting positive returns.

This new development—that US treasuries no longer offer CYA protection for equity investors in difficult times—is an important one. It makes allocating capital to either equities or bonds a lot more challenging. Or at least it becomes a lot more challenging if you are compelled to follow contemporary western society’s all-important guiding principle: CYA.

Continue reading at ZeroHedge.com, Click Here.