Feature your business, services, products, events & news. Submit Website.

Breaking Top Featured Content:

DoubleLine: The Pandora’s Box Of Fed’s Digital Currency Will Ignite An “Inflationary Conflagration”

Tyler Durden

Thu, 10/08/2020 – 16:30

We most recently described the Fed’s stealthy plan to deposit digital dollars to “each American” during the next crisis as a unprecedented monetary overhaul, but more importantly, a truly stealthy one: to be sure, there has barely been any media coverage of what may soon be a money transfer by the Fed – a direct stimulus to any and all Americans – in an attempt to spark inflation after years of losing the war with deflation.

That’s why we were happy to read that none other than Jeff Gundlach’s DoubleLine, one of the highest profile asset managers today, published a paper authored by fixed income portolio manager Bill Campbell exposing what it called “The Pandora’s Box of Central Bank Digital Currencies”, in which it echoed our claims, writing that “such a mechanism could open veritable floodgates of liquidity into the consumer economy and accelerate the rate of inflation. While central banks have been trying without success to increase inflation for the past decade, the temptation to put CBDCs into effect might be very strong among policymakers. However, CBDCs would not only inject liquidity into the economy but also could accelerate the velocity of money. That one-two punch could bring about far more inflation than central bankers bargain for.”

It then proceeds to blast this new development:

The temptations of CBDCs are not limited to excesses in monetary policy. CBDCs also appear to be an effective mechanism for bypassing the taxation, debt issuance and spending prerogatives of government to implement a quasi-fiscal policy. Imagine, for example, the ease of enacting Modern Monetary Theory via CBDCs. With CBDCs, the central banks would possess the necessary plumbing to directly deliver a digital currency to individuals’ bank accounts, ready to be spent via debit cards.

Which, of course, is precisely the intention and not only the beginning of the end of fiat and paper currencies but also the catalyst that will send alternative assets and especially gold soaring.

While the full note is below and we urge all readers to go over it, we will skip right to the end of Campbell’s paper in which he quotes from the former Philadelphia Fed president Charles Plosser who in 2012 warned of precisely this outcome:

“Once a central bank ventures into fiscal policy, it is likely to find itself under increasing pressure from the private sector, financial markets, or the government to use its balance sheet to substitute for other fiscal decisions.”

As Campbell correctly concludes, “with a flick of the digital switch, CBDCs can enable policymakers to meet, or cave in to, those demands – at the risk of igniting an inflation conflagration, abandoning what little still survives of sovereign fiscal discipline and who knows what else. I hope the leaders of the world’s central banks will approach this new financial technology with extreme caution, guarding against its overuse or outright abuse.”

We hope so too, but we know better: once it becomes available, it’s pretty much game over. The DoubleLine strategist shares that sentiment:

It’s hard to be optimistic. Soon our monetary Pandoras will possess their own box full of new powers, perhaps too enticing to resist.”

Translation: buy gold. Lots of it.

* * *

The full DoubleLine paper is below (pdf link):

The Pandora’s Box ofCentral Bank Digital Currencies

Over the past decade, central banks have added to their policy toolkit such practices as quantitative easing (QE) and, in Europe and Japan, negative interest rates. Formerly viewed as unconventional, these tools are now seen as necessary, even conventional, methods of monetary policy in a developed world struggling to produce inflation. For their next step into the unknown, central banks are readying a technology that could shatter what remains of the wall between sovereign government fiscal policy and central banking. This innovation is central bank digital currencies (CBDCs). These have the potential to become an inflation game changer, but the world’s central bankers should proceed with great caution. Implementation of CBDCs might open a Pandora’s box of unintended consequences, fiscal as well as monetary, overwhelming our would-be masters of money.

Disinflation: Bête Noire of the Central Banks

Inflation so far has not materialized in many developed markets, defying years of extraordinary policy efforts to stoke it. The European Central Bank (ECB) has failed to generate durable inflation at the targeted 2% level despite engaging in QE since March 2015 and implementing negative interest rate policy since June 2014. The Bank of Japan has failed to do so despite engaging in QE since March 2001 and negative rate policy since January 2016. Even the U.S. Federal Reserve has been unable to bring about stable inflation at 2% for a decent period of time despite engaging in QE since December 2008.

According to the quantity theory of money, large increases in money supplies should push inflation higher. Thus at the time QE was introduced in the U.K., Europe and the U.S., policymakers understandably were hopeful of achieving their inflation targets. Some observers in fact worried that QE might exceed those targets and trigger runaway inflation. Both those hopes and fears have proved premature. Instead, developed economies remain stuck in a disinflationary environment.

Observers have pointed to various causes of the conundrum of persistent disinflation. Demographics, technology and the growing stock of debt rank high among the troublemakers, but monetary levers have virtually no influence over the first two of these variables, and the third lies in the hands of sovereign government, not central banking. So I believe that central bankers are focusing on other disinflation culprits – namely, the entrapment of liquidity inside the banking system and the decline in the velocity of money. Their “solution” is the creation of CBDCs.

Velocity of Money and Liquidity Traps

The velocity of money is the rate at which money is exchanged in an economy through transactions between lenders and borrowers, buyers and sellers. If the number of transactions increases relative to the quantity of goods and services, prices should rise because the total amount of money in circulation has gone up. Conversely, if the number of transactions falls relative to the quantity of goods and services, sellers will reduce prices to try to make sales, pushing inflation down.

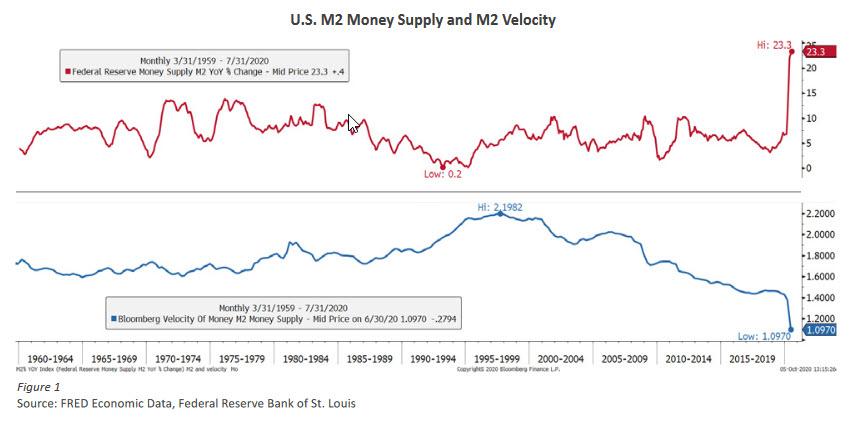

At its outset in the U.S. in December 2008, QE was expected to unleash an enormous amount of liquidity into the broader economy, raising the velocity of money and thus generating inflation. In fact, the opposite has happened. The liquidity produced by QE has become stuck inside the financial system, and the velocity of money has plummeted. The evidence from the monetary metrics could not be starker. As measured by the Federal Reserve’s M2 monetary aggregate, the U.S. money supply has soared to all-time highs. The velocity of M2, however, has declined and then plunged to all-time lows as GDP growth for years remained lackluster and then nosedived amid the COVID-19 lockdowns. (Figure 1)

To understand lackluster growth amid massive QE, it is important to remember that QE has expanded liquidity in the banking sector but not to the broader economy. At its heart, QE is a process whereby the central bank will “purchase” a bond from a bank and pay for that bond by crediting the bank’s excess reserve account. Excess reserves stay within the banking sector until used by banks for lending or market-making activity. Unfortunately, banks have grown more cautious in their lending practices. They have focused the majority of their credit extension to larger corporations, ignoring to a large extent smaller businesses, which employ most of the working population, and consumers.1 Fewer loans to such customers means less money in circulation in the economy.

Thus, much of the liquidity produced by QE has not found its way into the broader economy. Instead, this liquidity has served merely to drive up the value of stocks, bonds or other financial assets. Moreover, because central banks resort to QE during economically challenging times, when disinflationary or outright deflationary forces are at their greatest, the funneling of large excesses of liquidity into the banking system comes at the exact moment such banks are least likely to accelerate loan growth.

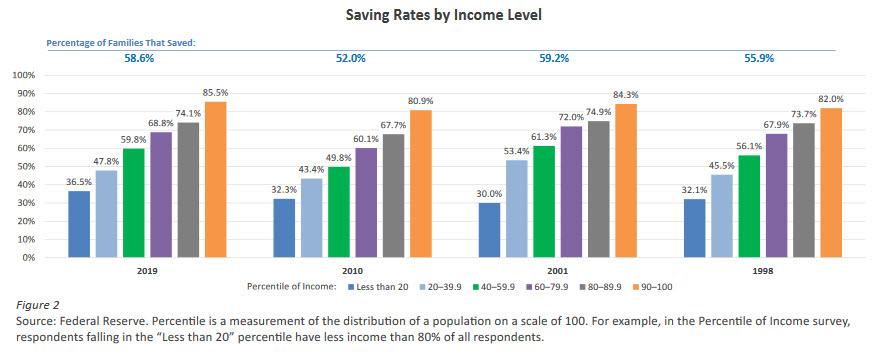

This dynamic adversely impacts the lower-income segments of the population, which have a much higher tendency to consume (usually out of necessity), in contrast to the wealthier segments that are characterized by much higher savings rates. (Figure 2) In a prior paper, I highlighted one method to address this issue by focusing more on lending to small and midsized enterprises.2 However, central banks are up to something new and different if not radical. If implemented, CBDCs have the potential to expand central banking beyond the scope of its traditional monetary province into fiscal policy.

Central Bank Digital Currencies

CBDCs have thus far been confined to the realm of research, but this is about to change. In a little-noticed press release on Sept. 9, Mastercard announced progress on a platform that will allow central banks to evaluate use cases for CBDCs. “The platform,” the release states, “enables simulation of issuance, distribution and exchange of CBDCs between banks, financial service providers and consumers.”3 If the central bank can distribute a digital currency into the consumer banking infrastructure to directly reach consumers, consumers can purchase goods and services with that currency via their Mastercard debit cards. In effect, CBDCs would circumvent the problem of rising risk aversion on the part of bankers. Not only would CBDCs represent a powerful new monetary tool, they are so unconventional as to be quasi-fiscal in nature.

The lines between fiscal and monetary policy have become ever more blurred by the need to use both instruments to help deal with the challenges of a growth shock, weak inflation, a weak jobs market and income inequality. Governments across the globe are dealing with rising deficits and debt stocks in the face of these demands, which can lead to authorities overreaching in the use of these powers. In 2012, Charles I. Plosser, then president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, warned of this mission creep. “In a world of fiat currency,” Mr. Plosser wrote, “central banks are generally assigned the responsibility for establishing and maintaining the value or purchasing power of the nation’s monetary unit of account. Yet, that task can be undermined or completely subverted if fiscal authorities independently set their budgets in a manner that ultimately requires the central bank to finance government expenditures with significant amounts of seigniorage in lieu of tax revenues or debt.”4

Eight years later, Mr. Plosser’s cautionary counsel seems démodé in policy circles. CBDCs had moved well beyond a handful of policy research departments even before the epiphenomena of the COVID-19 pandemic and population lockdowns. In a survey published in January, the Bank of International Settlements reported that 80% of the world’s 66 central banks were engaged in some sort of work on digital currencies.5

Although its Governing Council has not decided on whether to move forward with a CBDC, the ECB appears to be laying its groundwork. In an Oct. 2 news release, the ECB announced the publication of a “comprehensive report on the possible issuance of a digital euro” by the Eurosystem High-Level Task Force on central bank digital currency, a unit comprising representatives of the ECB and the 19 central banks in the euro area. A public consultation on the digital euro will begin Oct. 12. “A digital euro,” according to the news release, “would be an electronic form of central bank money accessible to all citizens and firms – like banknotes, but in a digital form – to make their daily payments in a fast, easy and secure way. It would complement cash, not replace it.”6

In the U.S., Cleveland Fed President Loretta J. Mester stated in a Sept. 23 speech, “Legislation has proposed that each American have an account at the Fed in which digital dollars could be deposited, as liabilities of the Federal Reserve Banks, which could be used for emergency payments.”7

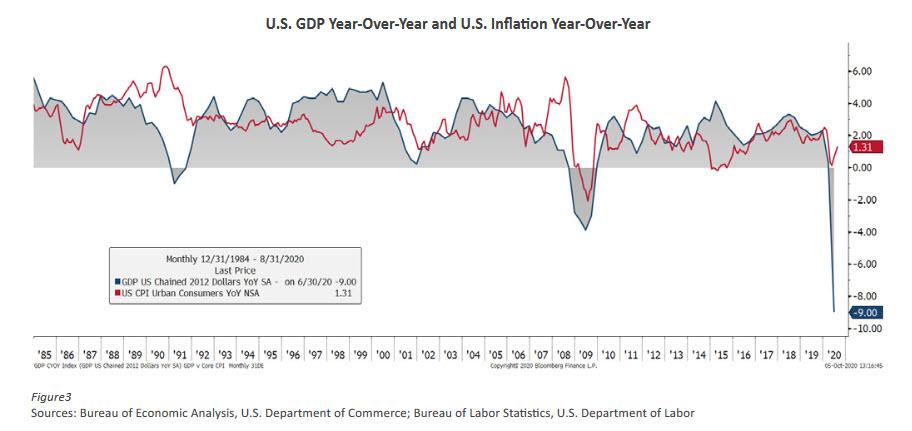

It is not a big leap from this statement to envision how one could extend such emergency payments to all sorts of policy goals or even political considerations, such as the growing consternation around wealth and income inequality. Historically, it has been up to recognized fiscal authorities to distribute money, or redistribute wealth, in this fashion. Given the persistence of the COVID-19 crisis and the potential for a fall resurgence in cases, concomitant curbs in economic activity (i.e., further lockdowns) could unleash a deflationary shock to the economy. Indeed, a demand shock puts significant downward pressure on inflation as producers lose pricing power when consumers stop purchasing because they’ve lost their jobs or cannot go out and spend money in any case. The past several decades provided ample evidence of the negative impact of falling economic activity on prices. (Figure 3)

Yet the policy implications are what we must keep an eye on as new digital policy tools become available to central bankers. Central banks and other financial institutions appear to be well along in the process of developing CBDCs. In the event of a new demand and disinflation shock, it is likely central banks will use them.

Floodgates (Monetary, Fiscal and Political)

With QE, central banks have printed excess reserves that have benefited only the very wealthy and large institutions. The innovation of a digital currency system as described by Mastercard could deliver stimulus directly to consumers. Such a mechanism could open veritable floodgates of liquidity into the consumer economy and accelerate the rate of inflation. While central banks have been trying without success to increase inflation for the past decade, the temptation to put CBDCs into effect might be very strong among policymakers. However, CBDCs would not only inject liquidity into the economy but also could accelerate the velocity of money. That one-two punch could bring about far more inflation than central bankers bargain for.

When first implementing QE, central banks promised that this measure would be temporary and would be unwound after the crisis ended, a pledge that I have doubted for a while.8 Central banks as we know have perpetuated QE as part of their updated toolbox of monetary policies. The first use of digital currencies in monetary policy might start small as policymakers, out of caution, seek to calibrate this experiment in quasi-fiscal stimulus. However, such initial restraint could give way to growing complacency and greater use of the tool – just as we saw with QE. The temptations of CBDCs are not limited to excesses in monetary policy. CBDCs also appear to be an effective mechanism for bypassing the taxation, debt issuance and spending prerogatives of government to implement a quasi-fiscal policy. Imagine, for example, the ease of enacting Modern Monetary Theory via CBDCs. With CBDCs, the central banks would possess the necessary plumbing to directly deliver a digital currency to individuals’ bank accounts, ready to be spent via debit cards.

Let me quote again from Charles I. Plosser’s warning in 2012: “Once a central bank ventures into fiscal policy, it is likely to find itself under increasing pressure from the private sector, financial markets, or the government to use its balance sheet to substitute for other fiscal decisions.” With a flick of the digital switch, CBDCs can enable policymakers to meet, or cave in to, those demands – at the risk of igniting an inflation conflagration, abandoning what little still survives of sovereign fiscal discipline and who knows what else. I hope the leaders of the world’s central banks will approach this new financial technology with extreme caution, guarding against its overuse or outright abuse. It’s hard to be optimistic. Soon our monetary Pandoras will possess their own box full of new powers, perhaps too enticing to resist.

Citations:

1 Bill Campbell, “Large Firms Reap Benefits From Central Bank Ease,” RealClearMarkets.com, August 18, 2020. https://www.realclearmarkets.com/2020/08/18/large_firms_reap_benefits_f…

2 Ibid.

3 “Mastercard Launches Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) Testing Platform, Enabling Central Banks to Assess and Explore National Digital Currencies,” Mastercard news release, Sept. 9, 2020 https://mastercardcontentexchange.com/newsroom/press-releases/2020/sept…

4 “Fiscal Policy and Monetary Policy: Restoring the Boundaries,” 2012 Annual Report, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia https://www.philadelphiafed.org/publications/annual-report/2012/restori…

5 “Impending arrival – a sequel to the survey on central bank digital currency,” Bank of International Settlements, January 2020 https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap107.pdf

6 “ECB intensifies its work on a digital euro,” European Central Bank news release, October 2, 2020. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/pr/date/2020/html/ecb.pr201002~f90bfc94…

7 “Payments and the Pandemic,” Sept. 23, 2020 https://www.clevelandfed.org/en/newsroom-and-events/speeches/sp-2020092…

8 Bill Campbell, “Quantitative Easing: Welcome to the Hotel California,” DoubleLine.com, Dec. 28, 2018. https://doubleline.com/dl/wp-content/uploads/Campbell_HotelCalifornia.p…

Continue reading at ZeroHedge.com, Click Here.