Feature your business, services, products, events & news. Submit Website.

Breaking Top Featured Content:

Designing And Building A Progressive Web Application Without A Framework (Part 1)

Designing And Building A Progressive Web Application Without A Framework (Part 1)

Ben Frain

How does a web application actually work? I don’t mean from the end-user point of view. I mean in the technical sense. How does a web application actually run? What kicks things off? Without any boilerplate code, what’s the right way to structure an application? Particularly a client-side application where all the logic runs on the end-users device. How does data get managed and manipulated? How do you make the interface react to changes in the data?

These are the kind of questions that are simple to side-step or ignore entirely with a framework. Developers reach for something like React, Vue, Ember or Angular, follow the documentation to get up and running and away they go. Those problems are handled by the framework’s box of tricks.

That may be exactly how you want things. Arguably, it’s the smart thing to do if you want to build something to a professional standard. However, with the magic abstracted away, you never get to learn how the tricks are actually performed.

Don’t you want to know how the tricks are done?

I did. So, I decided to try building a basic client-side application, sans-framework, to understand these problems for myself.

But, I’m getting a little ahead of myself; a little background first.

Before starting this journey I considered myself highly proficient at HTML and CSS but not JavaScript. As I felt I’d solved the biggest questions I had of CSS to my satisfaction, the next challenge I set myself was understanding a programming language.

The fact was, I was relatively beginner-level with JavaScript. And, aside from hacking the PHP of WordPress around, I had no exposure or training in any other programming language either.

Let me qualify that ‘beginner-level’ assertion. Sure, I could get interactivity working on a page. Toggle classes, create DOM nodes, append and move them around, etc. But when it came to organizing the code for anything beyond that I was pretty clueless. I wasn’t confident building anything approaching an application. I had no idea how to define a set of data in JavaScipt, let alone manipulate it with functions.

I had no understanding of JavaScript ‘design patterns’ — established approaches for solving oft-encountered code problems. I certainly didn’t have a feel for how to approach fundamental application-design decisions.

Have you ever played ‘Top Trumps’? Well, in the web developer edition, my card would look something like this (marks out of 100):

- CSS: 95

- Copy and paste: 90

- Hairline: 4

- HTML: 90

- JavaSript: 13

In addition to wanting to challenge myself on a technical level, I was also lacking in design chops.

With almost exclusively coding other peoples designs for the past decade, my visual design skills hadn’t had any real challenges since the late noughties. Reflecting on that fact and my puny JavaScript skills, cultivated a growing sense of professional inadequacy. It was time to address my shortcomings.

A personal challenge took form in my mind: to design and build a client-side JavaScript web application.

On Learning

There has never been more great resources to learn computing languages. Particularly JavaScript. However, it took me a while to find resources that explained things in a way that clicked. For me, Kyle Simpson’s ‘You Don’t Know JS’ and ‘Eloquent JavaScript’ by Marijn Haverbeke were a big help.

If you are beginning learning JavaScript, you will surely need to find your own gurus; people whose method of explaining works for you.

The first key thing I learned was that it’s pointless trying to learn from a teacher/resource that doesn’t explain things in a way you understand. Some people look at function examples with foo and bar in and instantly grok the meaning. I’m not one of those people. If you aren’t either, don’t assume programming languages aren’t for you. Just try a different resource and keep trying to apply the skills you are learning.

It’s also not a given that you will enjoy any kind of eureka moment where everything suddenly ‘clicks’; like the coding equivalent of love at first sight. It’s more likely it will take a lot of perseverance and considerable application of your learnings to feel confident.

As soon as you feel even a little competent, trying to apply your learning will teach you even more.

Here are some resources I found helpful along the way:

- Fun Fun Function YouTube Channel

- Kyle Simpson Plural Sight courses

- Wes Bos’s JavaScript30.com

- Eloquent JavaScript by Marijn Haverbeke

Right, that’s pretty much all you need to know about why I arrived at this point. The elephant now in the room is, why not use a framework?

Why Not React, Ember, Angular, Vue Et Al

Whilst the answer was alluded to at the beginning, I think the subject of why a framework wasn’t used needs expanding upon.

There are an abundance of high quality, well supported, JavaScript frameworks. Each specifically designed for the building of client-side web applications. Exactly the sort of thing I was looking to build. I forgive you for wondering the obvious: like, err, why not use one?

Here’s my stance on that. When you learn to use an abstraction, that’s primarily what you are learning — the abstraction. I wanted to learn the thing, not the abstraction of the thing.

I remember learning some jQuery back in the day. Whilst the lovely API let me make DOM manipulations easier than ever before I became powerless without it. I couldn’t even toggle classes on an element without needing jQuery. Task me with some basic interactivity on a page without jQuery to lean on and I stumbled about in my editor like a shorn Samson.

More recently, as I attempted to improve my understanding of JavaScript, I’d tried to wrap my head around Vue and React a little. But ultimately, I was never sure where standard JavaScript ended and React or Vue began. My opinion is that these abstractions are far more worthwhile when you understand what they are doing for you.

Therefore, if I was going to learn something I wanted to understand the core parts of the language. That way, I had some transferable skills. I wanted to retain something when the current flavor of the month framework had been cast aside for the next ‘hot new thing’.

Okay. Now, we’re caught up on why this app was getting made, and also, like it or not, how it would be made.

Let’s move on to what this thing was going to be.

An Application Idea

I needed an app idea. Nothing too ambitious; I didn’t have any delusions of creating a business start-up or appearing on Dragon’s Den — learning JavaScript and application basics was my primary goal.

The application needed to be something I had a fighting chance of pulling off technically and making a half-decent design job off to boot.

Tangent time.

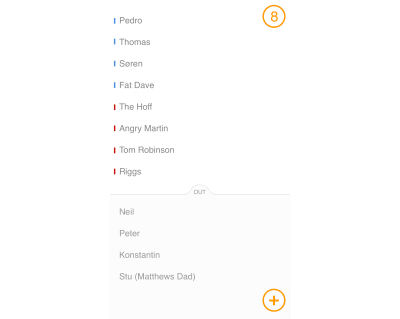

Away from work, I organize and play indoor football whenever I can. As the organizer, it’s a pain to mentally note who has sent me a message to say they are playing and who hasn’t. 10 people are needed for a game typically, 8 at a push. There’s a roster of about 20 people who may or may not be able to play each game.

The app idea I settled on was something that enabled picking players from a roster, giving me a count of how many players had confirmed they could play.

As I thought about it more I felt I could broaden the scope a little more so that it could be used to organize any simple team-based activity.

Admittedly, I’d hardly dreamt up Google Earth. It did, however, have all the essential challenges: design, data management, interactivity, data storage, code organization.

Design-wise, I wouldn’t concern myself with anything other than a version that could run and work well on a phone viewport. I’d limit the design challenges to solving the problems on small screens only.

The core idea certainly leaned itself to ‘to-do’ style applications, of which there were heaps of existing examples to look at for inspiration whilst also having just enough difference to provide some unique design and coding challenges.

Intended Features

An initial bullet-point list of features I intended to design and code looked like this:

- An input box to add people to the roster;

- The ability to set each person to ‘in’ or ‘out’;

- A tool that splits the people into teams, defaulting to 2 teams;

- The ability to delete a person from the roster;

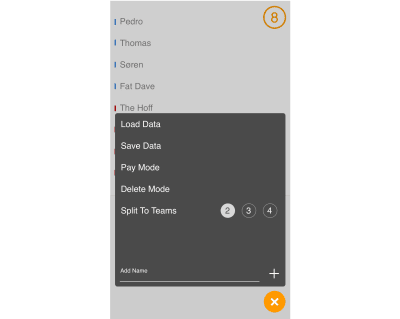

- Some interface for ‘tools’. Besides splitting, available tools should include the ability to download the entered data as a file, upload previously saved data and delete-all players in one go;

- The app should show a current count of how many people are ‘In’;

- If there are no people selected for a game, it should hide the team splitter;

- Pay mode. A toggle in settings that allows ‘in’ users to have an additional toggle to show whether they have paid or not.

At the outset, this is what I considered the features for a minimum viable product.

Design

Designs started on scraps of paper. It was illuminating (read: crushing) to find out just how many ideas which were incredible in my head turned out to be ludicrous when subjected to even the meagre scrutiny afforded by a pencil drawing.

Many ideas were therefore quickly ruled out, but the flip side was that by sketching some ideas out, it invariably led to other ideas I would never have otherwise considered.

Now, designers reading this will likely be like, “Duh, of course” but this was a real revelation to me. Developers are used to seeing later stage designs, rarely seeing all the abandoned steps along the way prior to that point.

Once happy with something as a pencil drawing, I’d try and re-create it in the design package, Sketch. Just as ideas fell away at the paper and pencil stage, an equal number failed to make it through the next fidelity stage of Sketch. The ones that seemed to hold up as artboards in Sketch were then chosen as the candidates to code out.

I’d find in turn that when those candidates were built-in code, a percentage also failed to work for varying reasons. Each fidelity step exposed new challenges for the design to either pass or fail. And a failure would lead me literally and figuratively back to the drawing board.

As such, ultimately, the design I ended up with is quite a bit different than the one I originally had in Sketch. Here are the first Sketch mockups:

Even then, I was under no delusions; it was a basic design. However, at this point I had something I was relatively confident could work and I was chomping at the bit to try and build it.

Technical Requirements

With some initial feature requirements and a basic visual direction, it was time to consider what should be achieved with the code.

Although received wisdom dictates that the way to make applications for iOS or Android devices is with native code, we have already established that my intention was to build the application with JavaScript.

I was also keen to ensure that the application ticked all the boxes necessary to qualify as a Progressive Web Application, or PWA as they are more commonly known.

On the off chance you are unaware what a Progressive Web Application is, here is the ‘elevator pitch’. Conceptually, just imagine a standard web application but one that meets some particular criteria. The adherence to this set of particular requirements means that a supporting device (think mobile phone) grants the web app special privileges, making the web application greater than the sum of its parts.

On Android, in particular, it can be near impossible to distinguish a PWA, built with just HTML, CSS and JavaScript, from an application built with native code.

Here is the Google checklist of requirements for an application to be considered a Progressive Web Application:

- Site is served over HTTPS;

- Pages are responsive on tablets & mobile devices;

- All app URLs load while offline;

- Metadata provided for Add to Home screen;

- First load fast even on 3G;

- Site works cross-browser;

- Page transitions don’t feel like they block on the network;

- Each page has a URL.

Now in addition, if you really want to be the teacher’s pet and have your application considered as an ‘Exemplary Progressive Web App’, then it should also meet the following requirements:

- Site’s content is indexed by Google;

- Schema.org metadata is provided where appropriate;

- Social metadata is provided where appropriate;

- Canonical URLs are provided when necessary;

- Pages use the History API;

- Content doesn’t jump as the page loads;

- Pressing back from a detail page retains scroll position on the previous list page;

- When tapped, inputs aren’t obscured by the on-screen keyboard;

- Content is easily shareable from standalone or full-screen mode;

- Site is responsive across phone, tablet and desktop screen sizes;

- Any app install prompts are not used excessively;

- The Add to Home Screen prompt is intercepted;

- First load very fast even on 3G;

- Site uses cache-first networking;

- Site appropriately informs the user when they’re offline;

- Provide context to the user about how notifications will be used;

- UI encouraging users to turn on Push Notifications must not be overly aggressive;

- Site dims the screen when the permission request is showing;

- Push notifications must be timely, precise and relevant;

- Provides controls to enable and disable notifications;

- User is logged in across devices via Credential Management API;

- User can pay easily via native UI from Payment Request API.

Crikey! I don’t know about you but that second bunch of stuff seems like a whole lot of work for a basic application! As it happens there are plenty of items there that aren’t relevant to what I had planned anyway. Despite that, I’m not ashamed to say I lowered my sights to only pass the initial tests.

For a whole section of application types, I believe a PWA is a more applicable solution than a native application. Where games and SaaS arguably make more sense in an app store, smaller utilities can live quite happily and more successfully on the web as Progressive Web Applications.

Whilst on the subject of me shirking hard work, another choice made early on was to try and store all data for the application on the users own device. That way it wouldn’t be necessary to hook up with data services and servers and deal with log-ins and authentications. For where my skills were at, figuring out authentication and storing user data seemed like it would almost certainly be biting off more than I could chew and overkill for the remit of the application!

Technology Choices

With a fairly clear idea on what the goal was, attention turned to the tools that could be employed to build it.

I decided early on to use TypeScript, which is described on its website as “… a typed superset of JavaScript that compiles to plain JavaScript.” What I’d seen and read of the language I liked, especially the fact it learned itself so well to static analysis.

Static analysis simply means a program can look at your code before running it (e.g. when it is static) and highlight problems. It can’t necessarily point out logical issues but it can point to non-conforming code against a set of rules.

Anything that could point out my (sure to be many) errors as I went along had to be a good thing, right?

If you are unfamiliar with TypeScript consider the following code in vanilla JavaScript:

console.log(`${count} players`);

let count = 0;

Run this code and you will get an error something like:

ReferenceError: Cannot access uninitialized variable.

For those with even a little JavaScript prowess, for this basic example, they don’t need a tool to tell them things won’t end well.

However, if you write that same code in TypeScript, this happens in the editor:

I’m getting some feedback on my idiocy before I even run the code! That’s the beauty of static analysis. This feedback was often like having a more experienced developer sat with me catching errors as I went.

TypeScript primarily, as the name implies, let’s you specify the ‘type’ expected for each thing in the code. This prevents you inadvertently ‘coercing’ one type to another. Or attempting to run a method on a piece of data that isn’t applicable — an array method on an object for example. This isn’t the sort of thing that necessarily results in an error when the code runs, but it can certainly introduce hard to track bugs. Thanks to TypeScript you get feedback in the editor before even attempting to run the code.

TypeScript was certainly not essential in this journey of discovery and I would never encourage anyone to jump on tools of this nature unless there was a clear benefit. Setting tools up and configuring tools in the first place can be a time sink so definitely consider their applicability before diving in.

There are other benefits afforded by TypeScript we will come to in the next article in this series but the static analysis capabilities were enough alone for me to want to adopt TypeScript.

There were knock-on considerations of the choices I was making. Opting to build the application as a Progressive Web Application meant I would need to understand Service Workers to some degree. Using TypeScript would mean introducing build tools of some sort. How would I manage those tools? Historically, I’d used NPM as a package manager but what about Yarn? Was it worth using Yarn instead? Being performance-focused would mean considering some minification or bundling tools; tools like webpack were becoming more and more popular and would need evaluating.

Summary

I’d recognized a need to embark on this quest. My JavaScript powers were weak and nothing girds the loins as much as attempting to put theory into practice. Deciding to build a web application with vanilla JavaScript was to be my baptism of fire.

I’d spent some time researching and considering the options for making the application and decided that making the application a Progressive Web App made the most sense for my skill-set and the relative simplicity of the idea.

I’d need build tools, a package manager, and subsequently, a whole lot of patience.

Ultimately, at this point the fundamental question remained: was this something I could actually manage? Or would I be humbled by my own ineptitude?

I hope you join me in part two when you can read about build tools, JavaScript design patterns and how to make something more ‘app-like’.

(dm, yk, il)

(dm, yk, il)