Feature your business, services, products, events & news. Submit Website.

Breaking Top Featured Content:

SVG Web Page Components For IoT And Makers (Part 1)

SVG Web Page Components For IoT And Makers (Part 1)

Richard Leddy

The IoT market is still in its early stages, but gathering steam. We are at a cusp in the history of IoT. Markets are quadrupling in the course of five years, 2015 to 2020. For web developers, this IoT growth is significant. There is already a great demand for IoT web techniques.

Many devices will be spread out geospatially, and its owners will desire remote control and management. Full web stacks must be made in order to create channels for teleoperation. Also, the interaction will be with one or more IoT devices at a time. The interaction must be in the real time of the physical world.

This discussion delves into the interface requirements using Vue.js as a catalyst and illustrates one method of webpage to device communication out of many subsitutions.

Here are some of the goals planned for this discussion:

- Create a single page web app SPWA that hosts groups of IoT human-machine interfaces (we may call these “panel groups”);

- Display lists of panel group identifiers as a result of querying a server;

- Display the panels of a selected group as a result of a query;

- Ensure that the panel display is loaded lazily and becomes animated quickly;

- Ensure that panels synchronize with IoT devices.

IoT And The Rapid Growth Of Web Pages

The presentation of graphics for visualization and remote control of hardware along with synchronization of web pages with real-time physical processes are within the realm of web page problem solving inherent in this IoT future.

Many of us are beginning our search for IoT presentation techniques, but there are a few web standards along with a few presentation techniques that we can begin using now. As we explore these standards and techniques together, we can join this IoT wave.

Dashboards and data visualization are in demand. Furthermore, the demand for going beyond web pages that provide forms or display lists or textual content is high. The dashboards for IoT need to be pictographic, animated. Animations must be synchronized with real-time physical processes in order to provide a veridical view of machine state to users. Machine state, such as a flame burning or not, trumps application state and provides critical information to operators, perhaps even safety information.

The dashboards require more than the visualization of data. We have to keep in mind that the things part of IoT is devices that not only have sensors but also control interfaces. In hardware implementations, MCUs are extended with switches, threshold switches, parameter settings, and more. Still, web pages may take the place of those hardware control components.

Nothing new. Computer interfaces for hardware have been around for a long time, but the rapid growth of web page use for these interfaces is part of our present experience. WebRTC and Speech API are on a development path that started in 2012. WebSockets has been developing in a similar time frame.

IoT has been in our minds for a long time. IoT has been part of the human dialog since 1832. But, IoT and wireless as we are coming to know it was envisioned by Tesla around 1926. Forbes 2018 State of Iot tells us the current market focus for IoT. Of interest to web developers, the article calls out dashboards:

“IoT early adopters or advocates prioritize dashboards, reporting, IoT use cases that provide data streams integral to analytics, advanced visualization, and data mining.”

The IoT market is huge. This Market Size article gives a prediction for the number of devices that will appear: 2018: 23.14 billion ⇒ 2025: 75.44 billion. And, it attempts to put a financial figure on it: 2014: $2.99 trillion ⇒ 2020: $8.90 trillion. The demand for IoT skills will be the fastest growing: IoT in Demand.

As we develop clear interfaces for controlling and monitoring devices, we encounter a new problem for developing our interfaces. All the many billions of devices will be owned by many people (or organizations). Also, each person may own any number of devices. Perhaps even some of the devices will be shared.

Modern interfaces that have been made for machine controls often have a well-defined layout specific to a particular machine or installation of a few machines. For instance, in a smart house, a high-end system will have an LCD with panels for carefully placed devices. But, as we grow with the web version of IoT, there will be any number of panels for a dynamic and even mobile stream of devices.

The management of panels for devices becomes similar to managing social connections on social web sites.

“Our user interfaces will have to be dynamic in managing which highly animated real-time panel must be displayed at any one time for each particular user.”

The dashboard is a single page web app SPWA. And, we can imagine a database of panels. So, if a single user is going to access a number of panels and configurations for his devices strewn about the planet, the SPWA needs to access panel components on demand. The panels and some of their supporting JavaScript will have to load lazily.

“Our interfaces will have to work with web page frameworks that can allow incorporating asynchronous component bindings without reinitializing their frameworks.”

Let’s use Vue.js, WebSockets, MQTT, and SVG to make our step into the IoT market.

Recommended reading: Building An Interactive Infographic With Vue.js

High-Level Architecture For An IoT Web App

When designing the interface for the IoT web page, one always has many options. One option might be to dedicate one single page to one single device. The page might even be rendered on the server side. The server would have the job of querying the device to get its sensor values and then putting the values into the appropriate places in the HTML string.

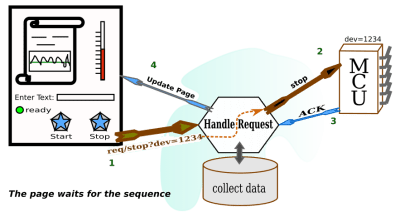

Many of us are familiar with tools that allow HTML templates to be written with special markers that indicate where to put variable values. Seeing {{temperature}} in such a template tells us and the view engine to take the temperature queried from a device and replace the {{temperature}} symbol with it. So, after waiting for the server to query the device, the device responding, rendering the page, and delivering the page, the user will finally be able to see the temperature reported by the device.

For this page per device architecture, the user may then wish to send a command to the device. No problem, he can fill out an HTML form and submit. The server might even have a route just for the device, or perhaps a little more cleverly, a route for the type of device and device ID. The server would then translate the form data into a message to send to the device, write it to some device handler and wait for an acknowledgment. Then, the server may finally respond to the post request and tell the user that everything is fine with the device.

Many CMSs work in this way for updating blog entries and the like. Nothing seems strange about it. It seems that HTML over HTTP has always had the design for getting pages that have been rendered and for sending form data to be handled by the web server. What’s more, there are thousands of CMS’s to choose from. So, in order to get our IoT system up, it seems reasonable to wade through those thousands of CMS’s to see which one is right for the job. Or, we might apply one filter on CMS’s to start with.

We have to take the real-time nature of what we are dealing with into consideration. So, while HTML in its original form is quite good for many enterprise tasks, it needs a little help in order to become the delivery mechanism for IoT management. So, we need a CMS or custom web server that helps HTML do this IoT job. We can also just think of the server as we assume CMS’s provide server functionality. We just need to keep in mind that the server has to provide event-driven animation, so the page can’t be 100% finalized static print.

Here are some parameters that might guide choices for our device-linked web page, things that it should do:

- Receive sensor data and other device status messages asynchronously;

- Render the sensor data for the page in the client (almost corollary to 1);

- Publish commands to a particular device or group of devices asynchronously;

- Optionally send commands through the server or bypass it.

- Securely maintain the ownership relationship between the device and the user;

- Manage critical device operation by either not interfering or overriding.

The list comes to mind when thinking about just one page acting as the interface to a selected device. We want to be able to communicate with the device freely when it comes to commands and data.

As for the page, we need only ask the web server for it once. We would expect that the web server (or associated application) would provide a secure communication pathway. And, the pathway does not have to be through the server, or maybe it should avoid the server altogether as the server may have higher priority tasks other than taking care of one page’s communication for data coming from sensors.

In fact, we can imagine data coming in from a sensor once a second, and we would not expect the web server itself to provide a constant second by the second update for thousands of individual sensor streams multiplied by thousands of viewers. Of course, a web server can be partitioned or set up in a load balancing framework, but there are other services that are customized for sensor delivery and marshaling commands to hardware.

The web server will need to deliver some packet so that the page may establish secure communication channels with the device. We have to be careful about sending messages on channels that don’t provide some management of the kinds of messages going through. There has to be some knowledge as to whether a device is in a mode that can be interrupted or there may be a demand for user action if a device is out of control. So, the web server can help the client to obtain the appropriate resources which can know more about the device. Messaging could be done with something like an MQTT server. And, there could be some services for preparing the MQTT server that can be initiated when the user gains access to his panel via the web server.

Because of the physical world with its real-time requirements and because of additional security considerations, our diagram becomes a little different from the original.

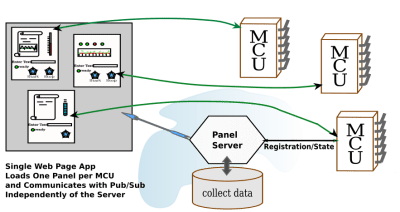

We don’t get to stop here. Setting up a single page per device, even if it is responsive and handles communication well, is not what we asked for. We have to assume that a user will log in to his account and access his dashboard. From there, he will ask for some list of content projects (most likely projects he is working on). Each item in the list will refer to a number of resources. When he selects an item by clicking or tapping, he will gain access to a collection of panels, each of which will have some information about a particular resource or IoT device.

Any number of the panels delivered in response to the query generated as a result of the user’s interface action may be those panels that interact with live devices. So, as soon as a panel comes up, it will be expected to show real-time activity and to be able to send a command to a device.

How the panels are seen on the page is a design decision. They might be floating windows, or they might be boxes on a scrollable background. However that is presented, panels will be ticking off time, temperature, pressure, wind speed, or whatever else you can imagine. We expect the panels to be animated with respect to various graphic scales. Temperature can be presented as a thermometer, speed as a semicircular speed gauge, sound as a streaming waveform, and so on.

The web server has the job of delivering the right panels to the right user given queries to a database of panels and given that devices have to be physically available. What’s more, given that there will be many different kinds of devices, the panels for each device will likely be different. So, the web server should be able to deliver the pictographic information needed for rendering a panel. However, the HTML page for the dashboard should not have to be loaded with all the possible panels. There is no idea of how many there will be.

Here are some parameters that might guide choices for our dashboard page, things that it should do:

- Present a way of selecting groups of related device panels;

- Make use of simultaneous device communication mechanisms for some number of devices;

- Activate device panels when the user requests them;

- Incorporate lazily loaded graphics for unique panel designs;

- Make use of security tokens and parameters with respect to each panel;

- Maintain synchronicity with all devices under user inspection.

We can begin to see how the game changes, but in the world of dashboard design, the game has been changing a little bit here and there for some time. We just have to narrow ourselves down to some up to date and useful page development tools to get ourselves up and going.

Let’s start with how we can render the panels. This already seems like a big job. We are imagining many different kinds of panels. But, if you ever used a music DAW, you would see how they have used graphics to make panels look like the analog devices used by bands from long ago. All the panels in DAW’s are drawn by the plugins that operate on sound. In fact, a lot of those DAW’s plugins might use SVG to render their interfaces. So, we limit ourselves to handling SVG interfaces, which in turn can be any graphic we can imagine.

Choosing SVG For Panels

Of course, I like DAWs and would use that for an example, but SVG is a web page standard. SVG is a W3C standard. It is for carrying line drawings to the web pages. SVG used to be a second class citizen on the web page, required to live in iFrames. But, since HTML5, it has been a first class citizen. Perhaps, when SVG2 comes out, that it will be able to use form elements. For now, form elements are Foreign Objects in SVG. But, that should not stop us from making SVG the substrate for panels.

SVG can be drawn, stored for display, and it can be lazily loaded. In fact, as we explore the component system we will see that SVG can be used for component templates. In this discussion, we will be using Vue.js to make components for the panels.

Drawing SVG is not difficult, because there are many line drawing programs that are easy to get. If you spend the money, you can get Adobe Illustrator, which exports SVG. Inkscape has been a goto for SVG creation for some time. It is open source and works well on Linux, but can also be run on Mac and Windows. Then, there are several web page SVG editing programs that are open source, and some SaaS versions as well.

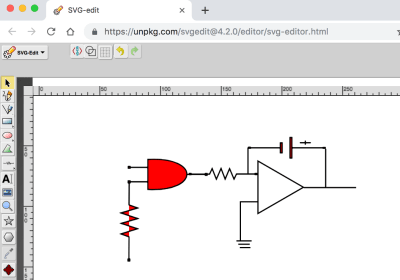

I have been looking around for an open-source web-based SVG editor. After some looking around, I came upon SVG-Edit. You can include it in your own web pages, perhaps if you are making an SVG based blog or something.

When you save your work to a file, SVG-Edit downloads it in your browser, and you can pick up the file from your download directory.

The picture I have drawn shows an AND gate controlling an integrator. That is not what one would usually expect to see in a panel for an MCU. The panel might have a button to feed one of the AND gate inputs, perhaps. Then it might have a display from an ADC that reads the output of the integrator. Perhaps that will be a line chart on a time axis. Most panels will have graphics that allow the user to relate to what is going on inside the MCU. And, if our circuit is going to live anywhere, it will be inside the MCU.

All the same, our electronic diagram can be used to discuss animation. What we want to do is take a look at the SVG and see where we can get at some of the DOM tags that we would like to change in some way. We can then animate the SVG by using a little vanilla JavaScript and a timer. Let’s make the AND gate blink in different colors.

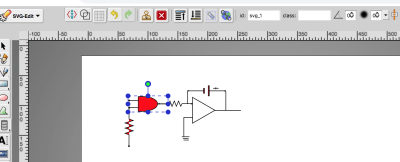

The SVG that we are looking for is in the following code box. It doesn’t look very friendly for the programmer, although the user will be quite happy. Nevertheless, there are still some cues to go on for finding which DOM element we wish to operate on. First, most SVG drawing tools have a way of getting at object properties, in particular, the id attribute. SVG-Edit has a way, too. In the editor, select the AND gate and observe the toolbar. You will see a field for the id and the CSS class as well.

If you can’t get to an editing tool for some reason, you can open the SVG up in a browser and inspect the DOM. In any case, we have found that our gate had id = “svg_1”.

All we need now is a little JavaScript. We do take note first that the element attribute “fill” is present. Then there is just the simple program that follows:

Notice that what we have is a minimal HTML page. You can cut and paste the code into your favorite editor. And, then don’t forget to cut and paste the SVG to replace the comment. My version of Chrome requires the page to be HTML in order to have the JavaScript section. So, that is one browser still treating SVG as something separate. But, it is a long way from the